Our Proud History

Our Proud History

We feel very fortunate to be members of a school that can trace its history over 350 years, a church that is over 450 years old and also to be part of a community that has such a long and fascinating story.

From the Romans to Manchester United; from the Norman conquest to the industrial revolution; from the upper classes to the working poor fighting for their rights; from war heroes to pacifists; from Empire builders to suffragettes; from a rural heath to a busy urban area.

Our school has been at the heart of Newton Heath for centuries, and served the children in all their spiritual and learning needs. Things have changed over the years, particularly over the last 150 years, and Newton Heath is transitioning from one identity to a new one, and it is a huge pleasure to be nurturing the next generation who will be part of it.

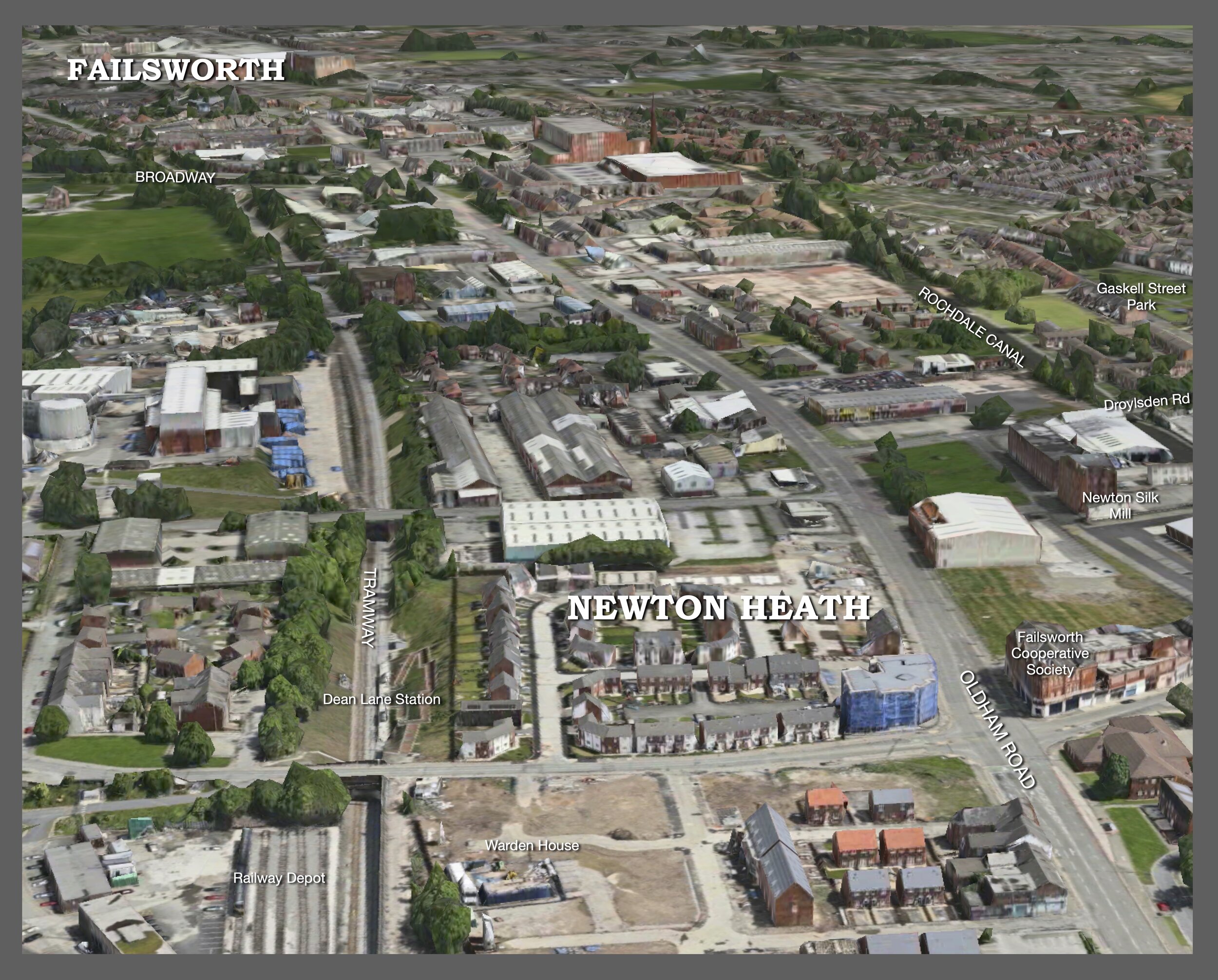

Newton Heath

Roman Times

A Roman road connecting Manchester and York ran straight through what is now Newton Heath. It is unmistakably a Roman road. The Roman agger (a type of ancient Roman rampart or embankment) on this road was huge and was too good a foundation to ignore for modern road builders.

Back Lane (now Briscoe Lane) and All Saints Church were actually built exactly on top of the old road. Roman Road in Failsworth, Briscoe Lane and Bradford Road were all part of one Roman road that eventually led to Deansgate and the fort in Castlefield.

This was part of a major inter-city highway for the Romans - Chester to York - and probably the most important road in northern England. The road features a long straight alignment from Store Street, Manchester, all the way to High Moor beyond Oldham. The route out of Manchester fort to join it perhaps would have been close to Whitworth Street.

Mamucium - Roman Manchester

Find out how the Roman Road underneath our church would have been constructed.

Fort similar to the one at Castleshaw outside of Oldham which was on the road to York.

Find out more about Roman roads.

An article in All Saints Parish magazine spoke of the road being made by laying large oak beams across the boggy parts along Briscoe Lane and in Gaskell Street, a farm labourer had found thirty oak logs so decayed that they could only be used for firewood.

“It crosses the very middle of Newton Heath, the chapel standing on the very ridge of it, standing at the west end of the chapel, you see the trace of it into Bradford lane. Standing at the East end you see the trace of it go behind a house and a barn on the East end of the common. It then runs through the enclosures to Mr Wagstaffs house where it enters alone and is visible enough.

In about 400 yards more, being interrupted by a moss, it rises with a prodigious grandeur and is the finest remains of a Roman Road in England that I ever saw. It is visible for half a mile more along a back lane leading to Hollingwood but on the lane turning to the common it strikes across a meadow of Mr Whitehead’s and is visible for a small part of it.”

Find out more about the Norman Conquest.

Clayton Hall

Clayton Hall was an extremely important residence in the Newton Chapelry District for centuries, and was also linked to Culcheth Hall, which used to be at the southern end of Culcheth Lane near the present day Christ the King Church.

The Manchester Collegiate Church (now Manchester Cathedral) owned much of the land in medieval Newton Heath, but the owners of Clayton Hall were also important land and property owners.

When Cecilia Clayton married Robert de Byron in 1194 Clayton Hall passed to the Byron family, of which poet Lord Byron was a later member. The Byrons lived there for more than 400 years, and owned much land within the Newton Chapelry, of which Clayton Hall was part of. Robert de Byron was a descendant of Ralph de Buron, who came over with William the Conqueror in 1066, and was given lands in Nottinghamshire.

Clayton Hall is still in existence and can be visited.

Find out more about the Magna Carta.

Find out more about the castles built when England was at war with Wales and Scotland.

There is some evidence to suggest that there was a chapel at Newton (Heath) in the early 1400s, and it was likely to have been dedicated to St. Mary the Virgin. This would have been a Catholic Church given it was before the reformation, when King Henry VIII created the Church of England and broke ties with the Roman Catholic Church and the Pope.

The Newton Chapel was constructed on top of the old Roman Road at the intersection of Back Lane (leading from Manchester towards Oldham), and the highway between Clayton and Moston. This position put the chapel at the highest point of the heath.

Find out more about the War of the Roses.

The Byrons sold Clayton Hall to the Chetham family in 1540. The Chethams would go on to establish the Chetham’s Hospital (now Chetham’s School of Music) and the Chetham’s Library (the oldest public library in the English-speaking world).

Find out about the Tower of London.

There are definite records for Newton Chapel in 1556, and a chapel constructed in 1571.

The Commonwealth period (when there was no King or Queen after the execution of Charles I) was a very testing one for Newton Chapel. It tested loyalties and many were resistant to the changes imposed by Oliver Cromwell’s leadership.

Beginning of All Saints School

There is no definite date for the start for Newton School (later All Saints School), but there is a recount of the master of the school in the grounds of the chapel during the Commonwealth period (1649 - 1660), and then a later record in 1679 for the death of James Hulme the school-master, who died suddenly in school, and was later buried in the chapel graveyard at the age of around 70.

In 1689, John Gilliam (of Culcheth Hall and Estate) gave £20 a year to the trustees Ralph Worsley and others, to teach 4 poor children at the school, and a new building was constructed. This was money was given by the will of Elizabeth Chetham, “for the religious education of poor children in the Townships of Moston and Newton until they could read the English bible and no longer.

The site of the original school was north of the old chapel and in 1698, the school-master was Samuel Mattley.

Find out about the Civil War.

The village of Newton Heath or Newton, was until the Industrial Revolution a small settlement based around four village greens surrounding the Heath, with much of its land owned by Manchester’s Collegiate Church.

Find out about industrialisation.

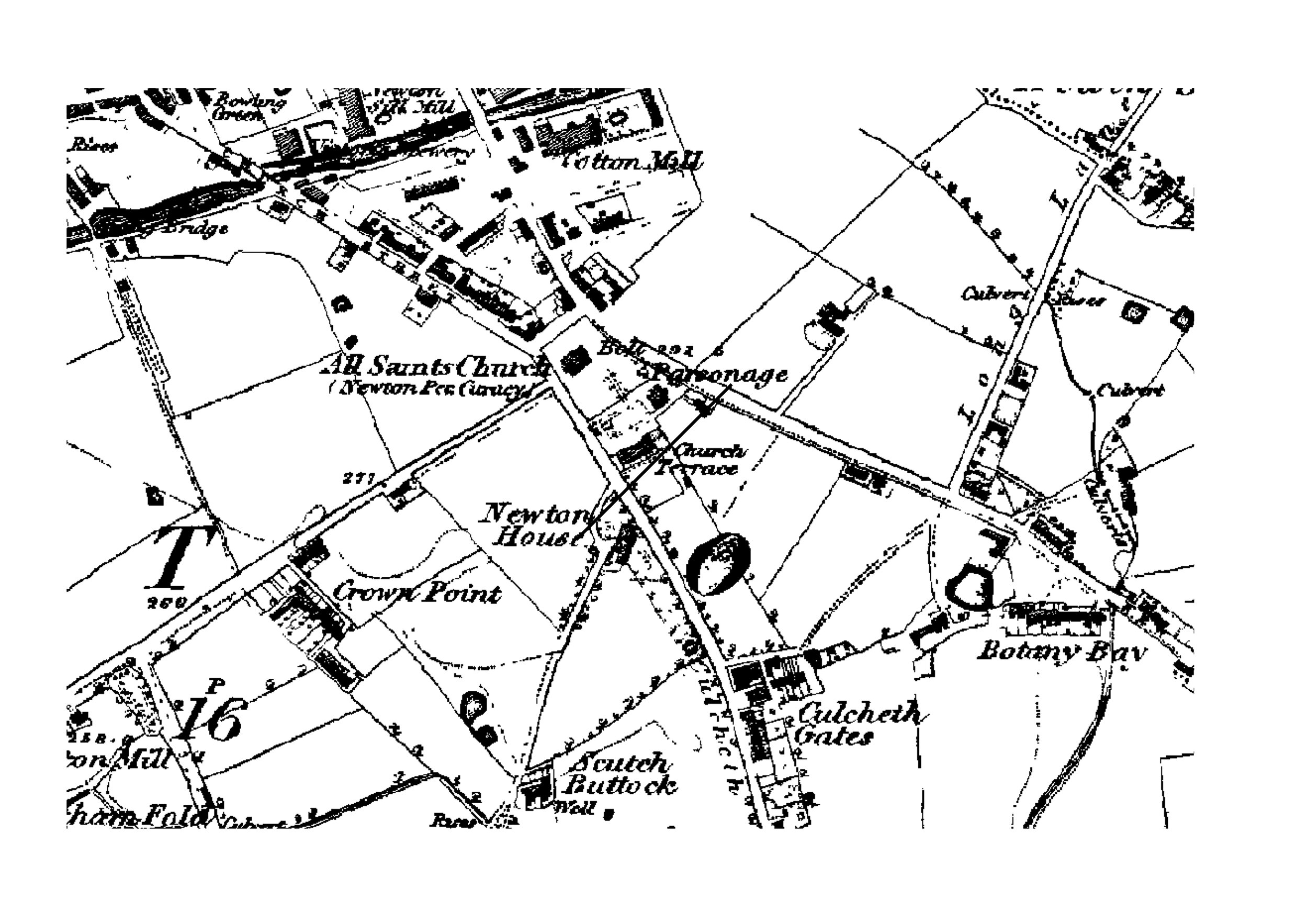

See where the old ‘heath’ would have been

Refurbishment for the School

“By his will dated September 15, 1763, Reverend William Purnell, incumbent of Newton, endowed the school with £200, for the purpose of instructing reading, writing, and accounts, fifteen poor boys and girls living in the Chapelry of Newton.”

In 1773, the school building had fallen into decay and could no longer be used. Lessons were then taken in the church while funds were raised for a new building. This new building was a little further north of the chapel and across a lane (now All Saints’ Street). This area between the chapel and the canal constructed in 1804 would be for the “poor” and included a “Poor House”.

“The old school at Newton was become so very ruinous, and so much out of repair as greatly to endanger the children’s health, if not their lives. Accordingly a subscription as opened and a new school rebuilt, but the subscription fell considerably short, and some of the bills yet unpaid. It is humbly requested that the ladies and gentlemen in and about Manchester in general, and the neighbourhood of Newton in particular, will exert themselves upon the charitable occasion, in order to free the said School from so disagreeable a debt, as they may be assured not a single shilling will be applied to any private Purpose whatsoever.”

“On Thursday evening died at Stockport, supposed by the sudden bursting of a blood vessel, the rev. William Jackson, M.A., chaplain to the earl of Hardwicke, one of the king’s preachers of the county of Lancaster, and minister of Newton, near this town. He was also minister of Denton in this parish, and master of the free grammar school in Stockport near forty years. His memory will be long revered by his surviving friends, relatives and hearers.

(He was appointed by the warden and fellows of Manchester Collegiate church to the perpetual curacy of Newton Heath on 23rd July 1789, on the death of Richard Milward.)”

“Aw’r gooien by th’ docthur’s shop

Ut top o’ Newton Yeah;

Un theer aw gan a sudden stop,

Un begun t’be fort o’ death.

Aw thaw aw seed the gallows tree,

Where th’ yarn-croft thief were swung;

Un ‘ot Owd Nick were takkin’ me

Un there he’d ha’ me hung.”

Before the 1814 church was constructed, the previous Newton chapels had earth floors and rushes were laid down on an annual basis to provide limited comfort to the congregation.

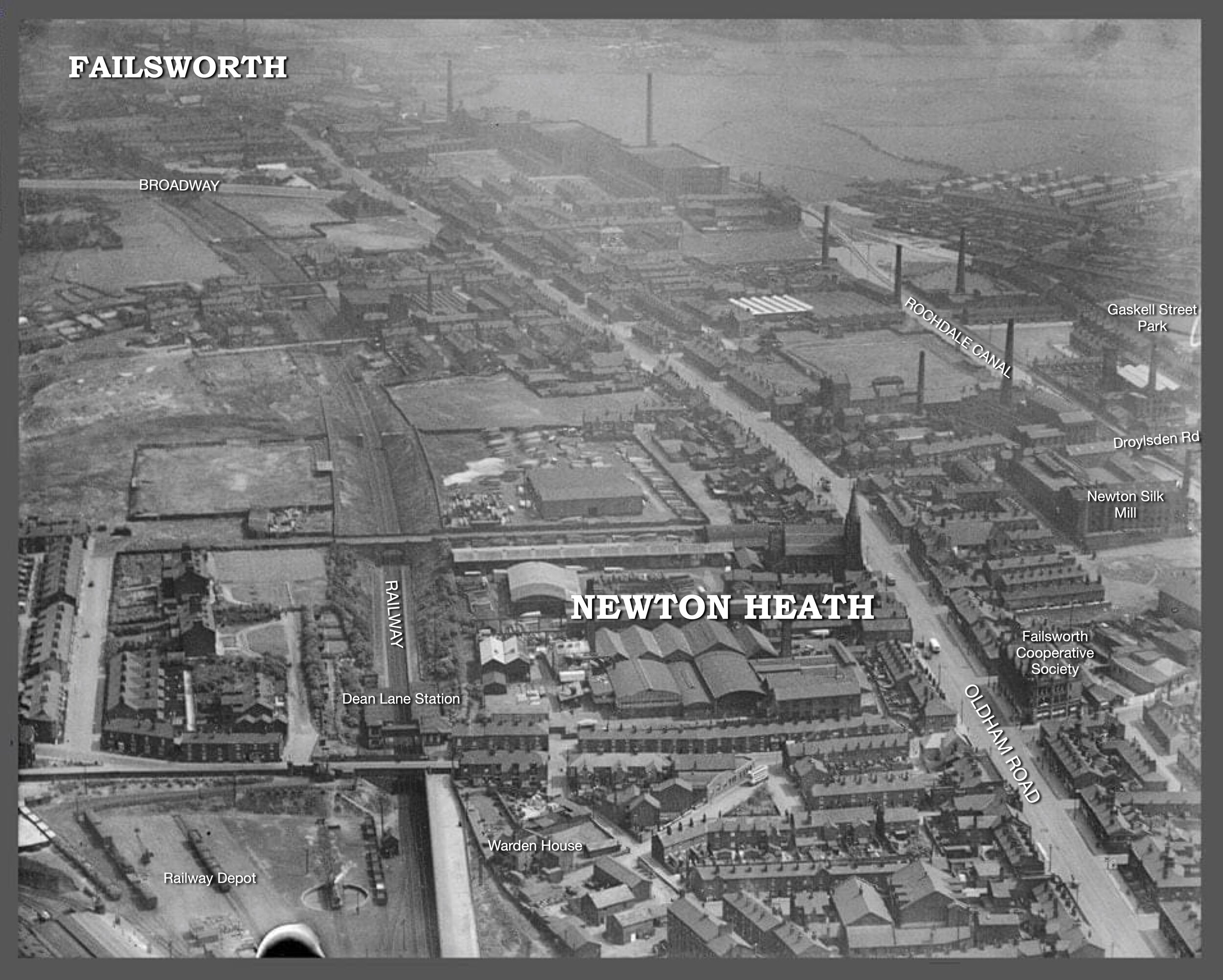

Urban Newton Heath exploded in the 1800s, driven by the opening of the Rochdale Canal in 1804 and the arrival of the railway 35 years later. This boosted the textile industries of silk weaving, cotton mills and bleaching, which were much smaller enterprises in the previous century.

The heath was enclosed by act of parliament in 1802 and a Warden House named to help protect it.

The area would later be the centre of heavy engineering which would expand jobs and housing.

Find out more about the Victorian era.

Fighting for Rights and Peterloo

The mass movement of people from the countryside to work and live in the rapidly expanding cities and towns like Newton Heath, brought with it opportunity and hardships.

A reduction in wages for cotton weavers in 1807 and 1808 led to riots and turnouts. In May 1808 the weavers of Manchester, Newton and other places visited Blackley and collected the shuttles to stop work, and carried the pieces unfinished back to the warehouses in Manchester.

“On May 24 and 28 1808, the turnout weavers met on St. George’s Field near Miles Platting, and on the second day the Riot Act was read, the military cleared the ground, killing one and wounding several. It was on this occasion that Joseph Hanson, a cotton manufacturer living in Strangeways Hall, an employer of many weavers in the neighbourhood, and late Lieut-Col of the Loyal Masonic Volunteer Rifle Corps, addressed the weavers sympathetically and declined to leave the ground. He was indicted, and in March 1809 was convicted of encouraging the weavers to hostile proceedings. On May 12th he was fined £100 and sentenced to six months’ imprisonment. He declined the weavers offer to pay the fine, and they subscribed 39,600 pennies (£165) for a silver cup which was presented to him in token of their gratitude. He died Sept. 7, 1811, aged 37 years, and was interred in the Unitarian burial ground at Strand, Pilkington.”

Sadly, the events of 1819 would be even more tragic with the event that would become known as “Peterloo”.

The “Blanket Meeting’ was held in March 1817 and the Peter’s Field Meeting, commonly known called “Peterloo” occurred on August 16, 1819, and Newton and Failsworth were strongly represented on each of these occasions, the drillings which preceded Peterloo taking place close at hand on White Moss in Moston.

The following is an account from Joseph Barrett who was a Newton Heath manufacturer who kept a warehouse in Manchester, and he saw Peterloo from a vantage point close to that of the magistrates.

“I am now come to give an account of the Manchester Massacre, or Peter Loo affair, as it was often called because it took place in St Peters Square.

It was on the 16 August 1819 that a meeting was announced to take place of Reformers at that place. A few days before Mr Jonathan Hobson, a merchant in that place, & he came to my brothers house, and asked if my eldest brother would obtain a room where it could be seen. My brother said he would try to do so, & fortunately he met with a gentleman that had an untenanted house nearly opposite to where the platform for the speakers was to be placed, & he gave my brother the key of it, & my brother brought it home, and gave it to Mr Hobson.

Mr Hobson got some refreshments taken to an upper room in the house, & on the morning of the meeting Mr Hobson, myself & eldest brother were together. We saw the people arrive, among whom were many young women, dressed in white. There were persons from all the neighbouring towns and villages, with flags and bands of music, & persons with long white rods, who seemed to be the directors of each separate procession, but no weapons of any [kind] not even walking sticks, for they had been left in some house before the men entered Manchester lest it might be thought they were weapons.

The people continued to arrive until the square was filled, & there were calculated to be 80,000 & they [were] all quite peacable and orderly. We were in one of the best positions to see the whole of the meeting, & all the proceedings. The speakers came about one o’clock on to the Platform & were about to address the meeting, when the Manchester Yeomanry began to come towards the Platform, headed by Meager a drill sergeant to Captain Withington, whom we knew, as he had often sold us yarn.

The Yeomanry looked very pale & frightened, except Captain Withington, who was – . The speakers were taken off the platform, & the people remained quiet. It was said that the riot act was read, but if so, no one seemed to know. It was said afterwards it had been read from a chamber window at some distance.

After the speakers had been removed, the people began to go away, and then the Yeomanry got courage, and began to strike the people, but no [Resistance?] was mad[e]. The confusion, and panic became general, & we continued at the window to watch the proceedings of the Yeomanry, but soon a soldier or two pointed a musket, & said that they would shoot us, unless we shut the window & went from it.

After some time we return[ed] when the Yeomanry were not to be seen, but the appearance of the square was such as it is impossible to give an adequate idea; there were heaps of people lying, who seemed dead, but had got into this state, by being stuck & frightened, though a many of them were wounded. All over the place there were Flags & several instruments lying. There were only two persons killed on the field, one was John Lees, whose father we knew, as he had supplied us with cotton weft, & he lived at Oldham. The other was a special constable from the Bulls Head in Manchester.

There were about three hundred stationed under the house where we were, & the Manchester & Cheshire Yeomanry were so drunk & excited that they did not know what they were doing. One thing I must mention that while the people were lying as I have stated, one of the Cathedral Ministers high in office, kept walking about in the field, & seemed highly pleased with the seen [sic], for he strutted about like a cock that had beaten his opponent. The Yeomanry after this brilient victory went completely mad; the[y] made about the streets of Manchester striking at every person, that was in their way, and even went to one Cotton Mill, & wished to strike the people that were coming out, & hacked at the doors to make them come out.

Myself and brother returned home very much astonished, & [amazed?] at the proceedings. After we got home persons who had been to the meeting began to pass our house, & to them that were wounded my brother Thomas gave money. The Yeomanry went about the streets of Manchester in the mad[d]ist manner. The morning after an ultra Tory came into our Warehouse, & my brother said to him: ‘You made sad work with the people yesterday.’ He replied, ‘We could do it better, if [we] had to do it again.’ My brother said, ‘How would you do it better?’ He answered, ‘by stopping up the end of the streets leading from the meeting, & planting cannon, & killing ever[y] devil of them.’ My brother then said: What would you do for workmen, after that?’ He made no reply.

There were about 80,000 persons assembled at the meeting. We had supplied the Colledge, & the Infirmary with Bed Ticking for some time, & the buyer for the Infirmary came in one day about a week before the Meeting & said, You have a large pile of Gray Ticks there, send them to the Infirmary. We did so, but my brother was surprised at this offhand order. We learned after that the Ticking were made up into beds in readiness for the wounded at Peterloo. This circumstance has not been related often before & I do it now to shew the extreme madness & ??? of the Tories at this time.”

The following account was told to the Oldham Chronicle by a ‘veteran’ of Peterloo in 1884.

“He lost his hat and shoe in the struggle, and was glad to get away so well. Coming home through Newton Heath some time after the massacre he met a man carrying a bundle of shoes and hats. These he had picked up after the field had been cleared, and with them he was supplying everyone he met who had lost such things. Our narrator said, he tried shoes and hats until he was fitted, and on leaving the hat and shoe distributor he was told by him to tell all who had lost such head and foot gear that they might have any he had that would fit them.”

Peterloo ‘veterans’ from Failsworth and Newton Heath at a reunion in 1884.

New Church

The previous chapel, before the church we know today, literally fell down shortly after a service. This led to the construction of a ‘new’ and rather grand stone church.

Architect’s engraving of his plans for the new church, These were modified before construction.

View of All Saints Church from Briscoe Lane

All Saints School Expands

The school master in 1817 was Joseph Fletcher and in 1821, the Reverend T. Gaskell, the Rector, set up the Newton Heath Day and Sunday School Trust.

The trust deed for All Saints Primary School was written in 1821 and states:

“From time immemorial there hath existed a School near Newton Chapel for the education of poor children belonging to the Chapelry of Newton, with a garden adjoining at the back.

...the School had lately been raised higher and enlarged and improved by subscription, and the Rev. Thomas Gaskell, perpetual curate, with the church-warden and overseers of Newton, with the sanction of the key payers, vested the School in Trustees to be conducted on Church principles, stipulating that the Sunday school which had been established by subscription in the Chapelry of Newton should be permitted to occupy the School on Sundays and on certain week-day evenings, in order that writing and accounts might be taught.

”

The hearse house which adjoined the School, was reserved for the Trustees appointed for the re-erection of Newton Chapel who had built it.

In a blank window space of one of three cottages, adjoining the easterly end of the 1854 School, there was an inscription which read:

“These houses were erected by legacy from Mr. Thomas Todd, late of Culcheth, for the support of the Newton Sunday school 1826””

In 1829, the School became a National Society School with a Deed of Union, still operative, 'that the Children are instructed in the liturgy and Catechism of the Established Church.' In 1833, the government were starting to take a greater interest and control of education, and provided grants to voluntary schools.

Arrival of the Railway

The railway came to Newton Heath in 1839, only 10 years after Stephenson’s “Rocket” had won the ”Rainhill Trials” and became the first engine on the Liverpool and Manchester Railway, the first major railway in the world.

The railway would accelerate development in Newton Heath, and would also provide us with probably our most famous claim to fame - the birthplace of Manchester United Football Club.

Public Health

In the middle of the 19th century, many people in Newton Heath wanted improvements in public health. The population of Newton Heath had increased very quickly, and the number of local industries were also putting pressure on the water supply, drainage, sewers and catering for the dead.

“The proceedings were characterised by great disorder, fierce disputes and angry personal altercations, few appearing to consider themselves bound to act with ordinary courtesy towards the promoters.”

There was a very strong argument within the area, with one side desperate for change, and the other wanting to keep control over services and taxes. The public health enquiry would take place and a number of significant changes were suggested and ultimately put into place.

New School

The school master in 1852 was James Worthington and a ‘new’ school, that stood within living memory in All Saints’ Street, was built in 1854. The previous school had become inadequate for the requirements of the neighbourhood, it was rebuilt by public subscription.

The previous school building on All Saints Street which is now the site of the war and peace memorials.

How it might look today.

“This new School...is a spacious and handsome brick erection in the Tudor style of architecture. The front elevation contains a row of eight window. It is divided into two storeys by a row of stone labels, five in number, inscribed “All Saints’ Church Day and Sunday Schools”. The uniformity and straightens of line is pleasantly broken by three roof gables and by stone castings, string-course, mullions, and transoms. The entrance and master’s residence are at the west end and a little recessed. They bear a stone shield label inscribed “Erected 1854”... (the school) is well fitted up and possesses all the appliances of the modern system of education.”

Birth of Manchester United

Newton Heath LYR Football Club would become Manchester United in 1902

In 1878 the Lancashire and Yorkshire Railway Company granted permission for the employees of its Carriage and Wagon department to start a football team, which was subsequently named Newton Heath LYR, with Frederick Attock appointed as this new club's president. LYR stood for "Lancashire & Yorkshire Railway" and was used to distinguish the team from their colleagues from the Motive Power Division, who were known as Newton Heath Loco. The team was funded by the railway company, who paid the lease on its first home ground, a field close to the railway yard on North Road. It is said that the players were "tough, diligent men who formed a powerful side"; they initially played games against other teams of railway workers, very few of which were recorded.

On the final night of a fund-raising bazaar in 1901 (Newton Heath FC were in financial trouble and had been relegated to the Second Division), the club’s mascot, a giant lemon and white-coloured St. Bernard dog called The Major, went missing.

The dog belonged to Newton Heath full-back and captain Harry Stafford and on match-days, it would be seen at the ground with a collection box around its neck. The dog’s disappearance started a chain of events that changed the course of history, turning an underperforming Second Division team on a brink of bankruptcy into the First Division champions in a space of just seven years.

Having wandered the streets of Manchester, The Major turned up at a restaurant, where he caught the attention of a wealthy local brewer and businessman, John Henry Davies. Eager to buy the dog for his daughter, Davies tracked down Stafford through an advert in the Manchester Evening News. The businessman's initial offer was rejected by the footballer, who refused to part with his beloved pet. However, with Newton Heath at severe risk of bankruptcy, Stafford eventually gave in and The Major became Davies’s dog, just in time for his daughter’s 12th birthday.

First footage of Manchester United shortly after changing their name from Newton Heath FC.

As a result, Davies became interested in the Heathens’ financial plight and together with four other investors, including Stafford, he rescued the club from bankruptcy and became its new chairman. On 26 April 1902, given that the team now had few ties with its origins; it was no longer based in Newton Heath, the new owners renamed the club Manchester United Football Club, after considering the alternative names "Manchester Celtic" and "Manchester Central". They also changed the team's colours to red and white.

Newton Heath Through the Victorian Era to the Present Day…

By the late 1800s and into the 20th Century, the government increased spending on schools. The school master in 1899 was Mr Joseph Priest, who very sadly tried to take his own life. He had been school master for many years, and this shows that mental health and wellbeing are not something new.

The old rectory and church viewed from Droylsden Road in 1895.

Find out more about ‘Votes for Women’.

Our church 1910

AVRO

A.V. Roe & Co (Avro) developed a large factory as part of their headquarters at the junction of Ten Acres Lane and Briscoe Lane (the building is still standing).

In the first half of the 20th century, Avro were responsible for some very important and famous aircraft. The most famous being the WW2 bomber, the Avro Lancaster. This aircraft started as the Avro Manchester, but was upgraded from 2 engines to 4 in 1941, and changed its name due to poor performance. Mr Sharp’s great uncle was killed in an Avro Manchester in January 1942, and one of his crew mates is buried in Failsworth Jewish Cemetery.

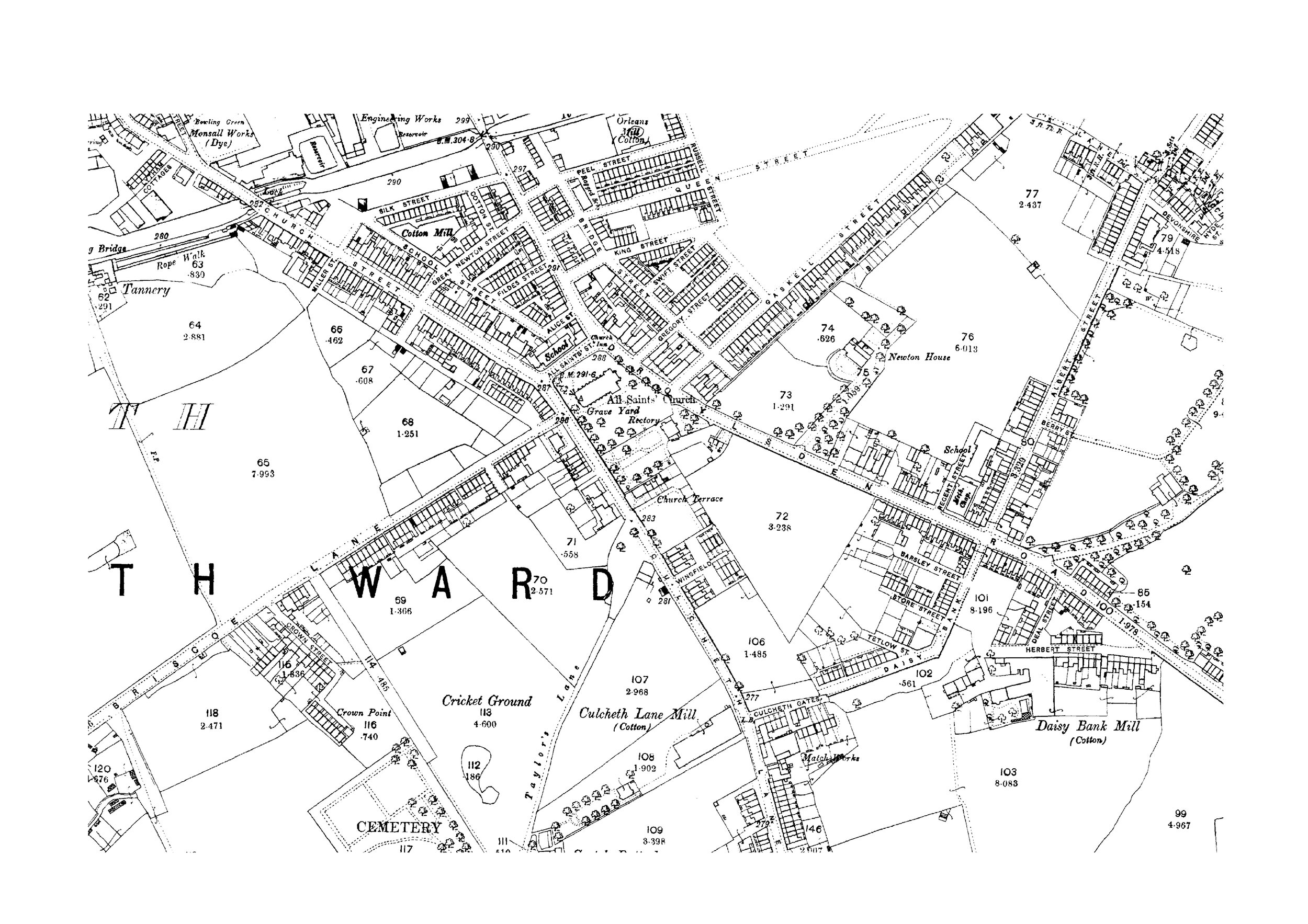

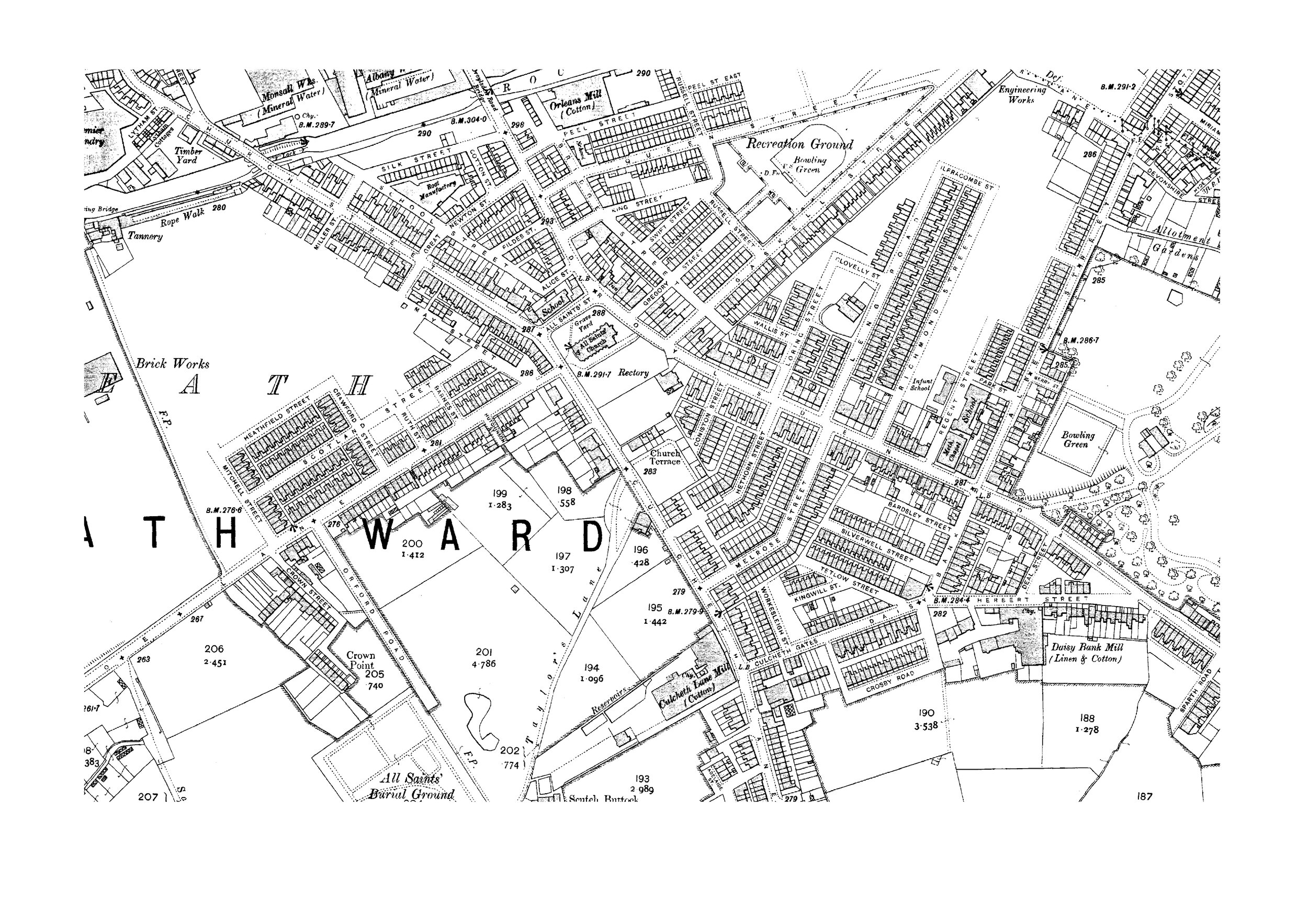

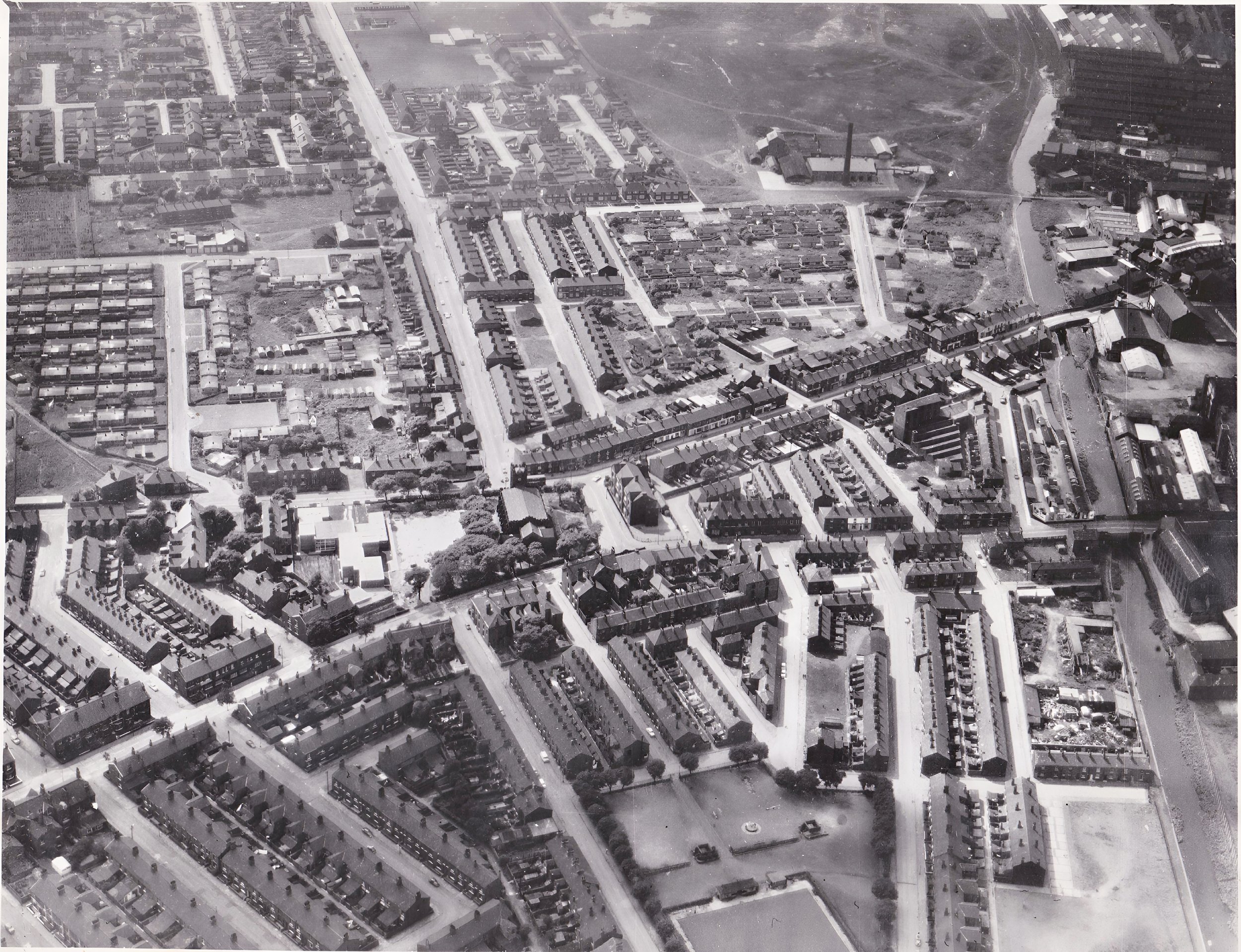

See how the landscape of Newton Heath has changed

Leaving a Legacy

Newton Heath has had many inspiring people living in it, and some of them were involved in great ‘battles’. Not all of these battles involved weapons though. Here are two examples of inspirational and brave characters with very different experiences.

Hannah Mitchell fought for the rights of women and the poor, but was a ‘pacifist’ meaning that she was against violence. Once she challenged Winston Churchill at a meeting in Manchester, and on another occasion was held in custody for protesting at a political meeting. She later went on to represent Newton Heath on the Manchester City Council.

George Stringer fought in World War 1 through the Middle East. He was the first person from Manchester to be awarded the Victoria Cross for valour in World War 1 and was presented to the Prince of Wales on a visit to the city.

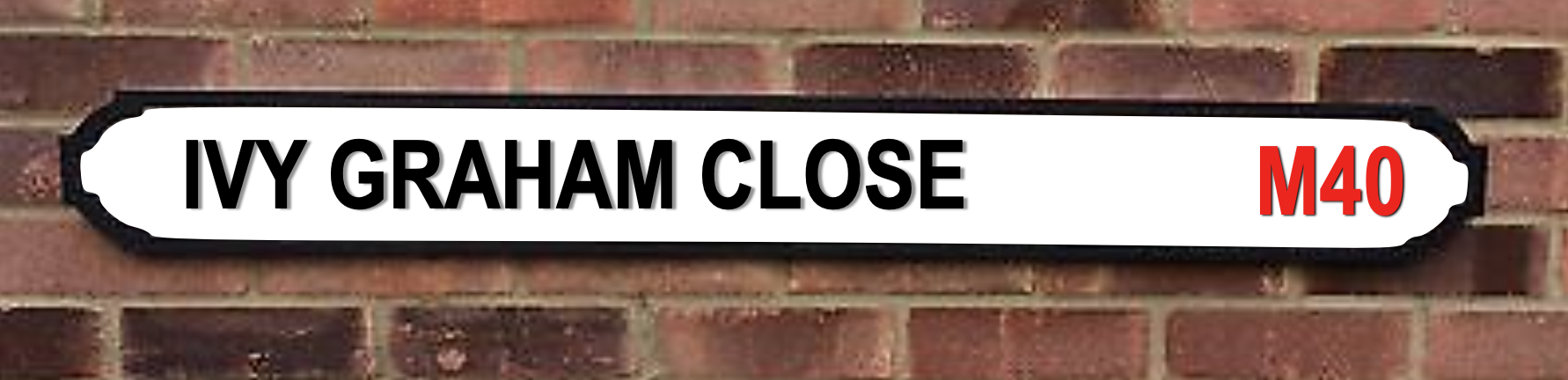

If you look around Newton Heath you will see many streets named in honour of important local figures.

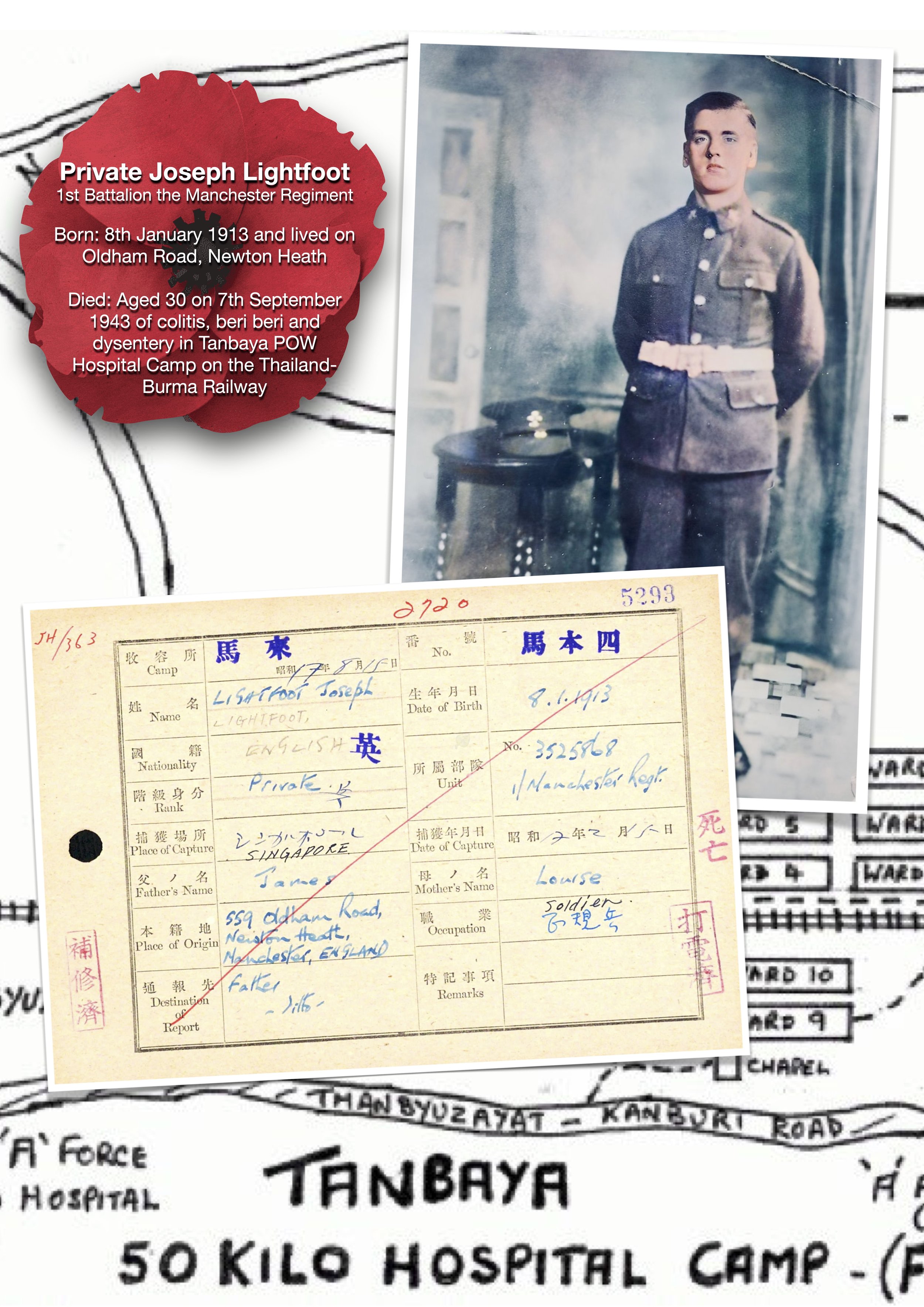

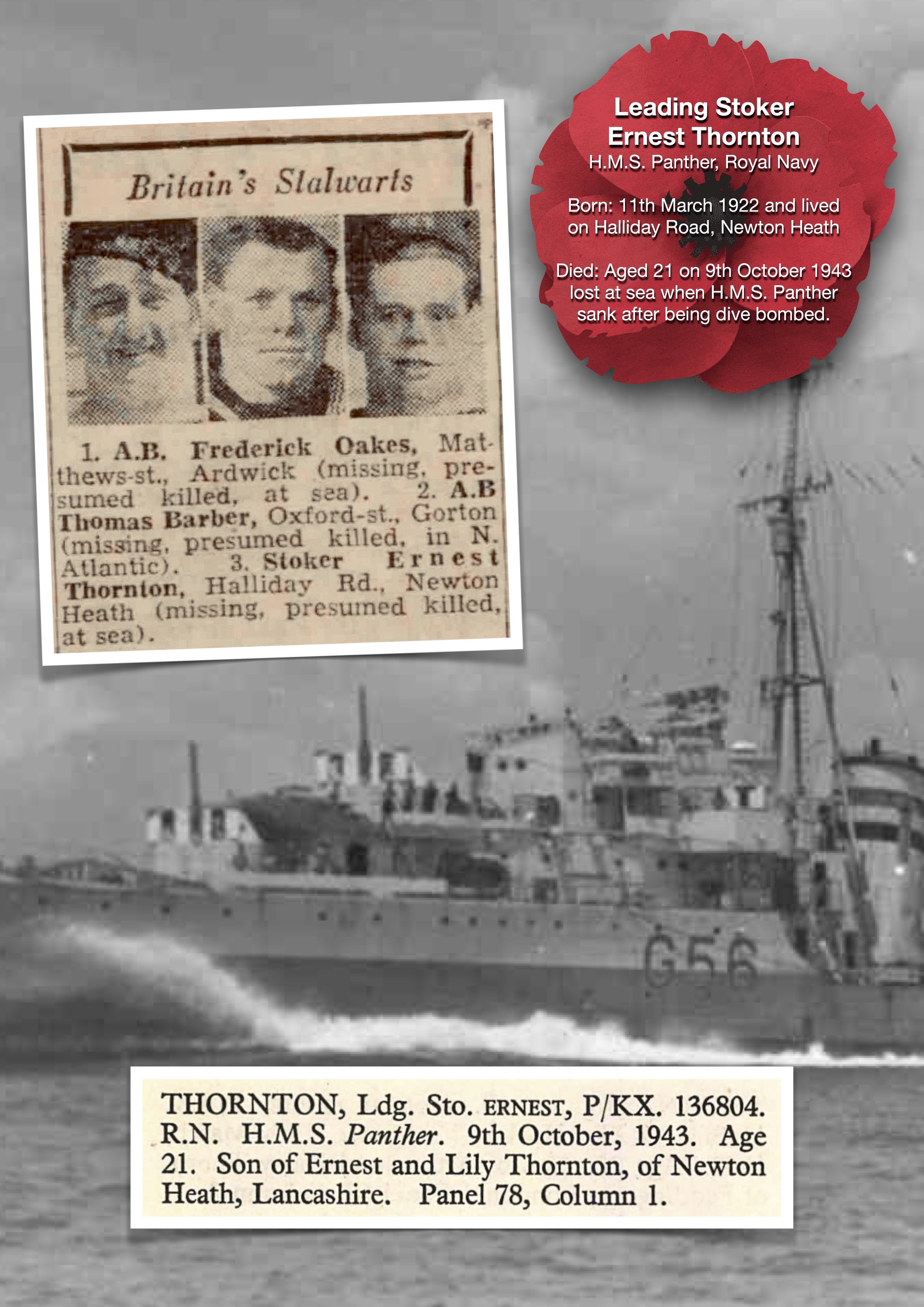

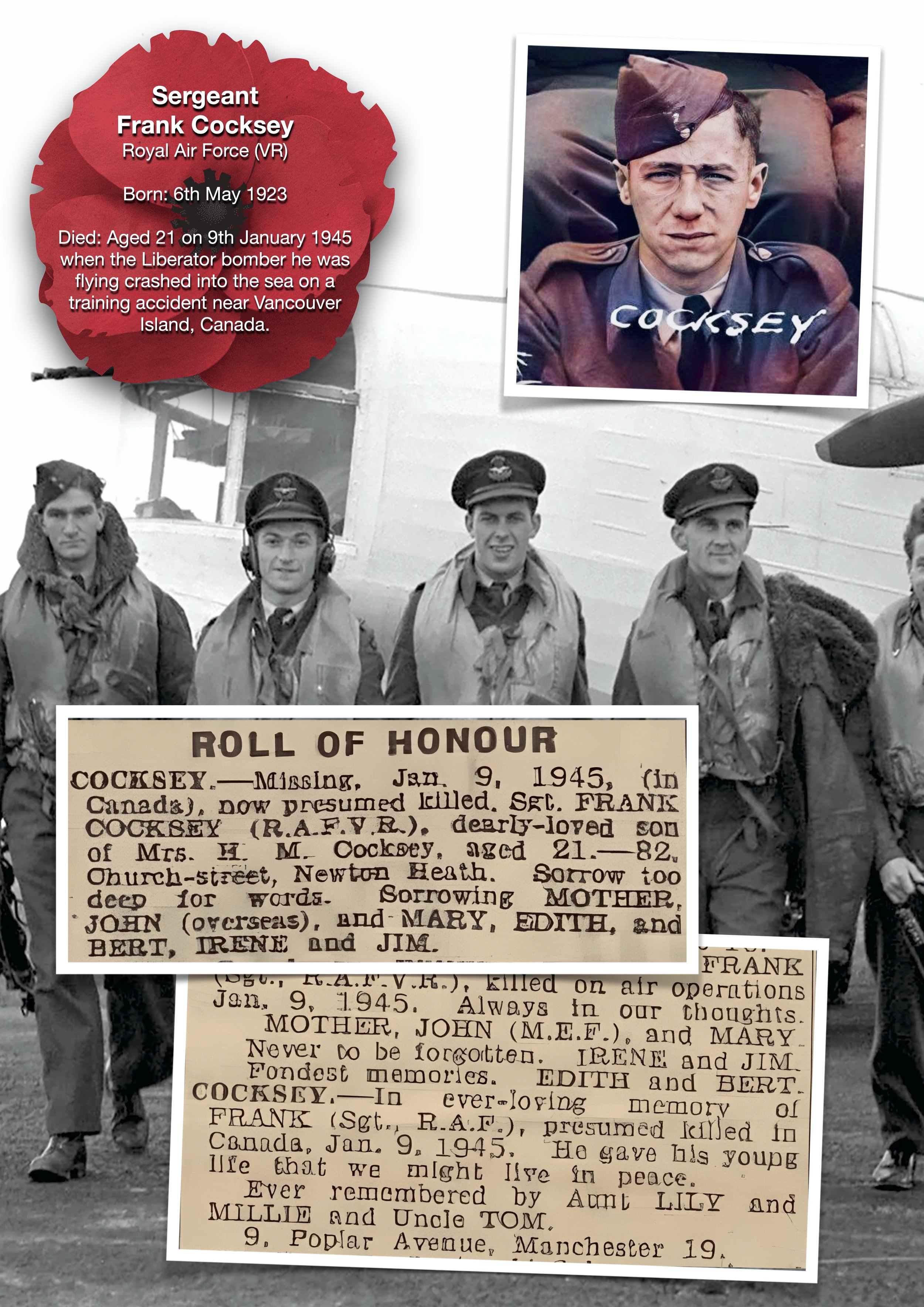

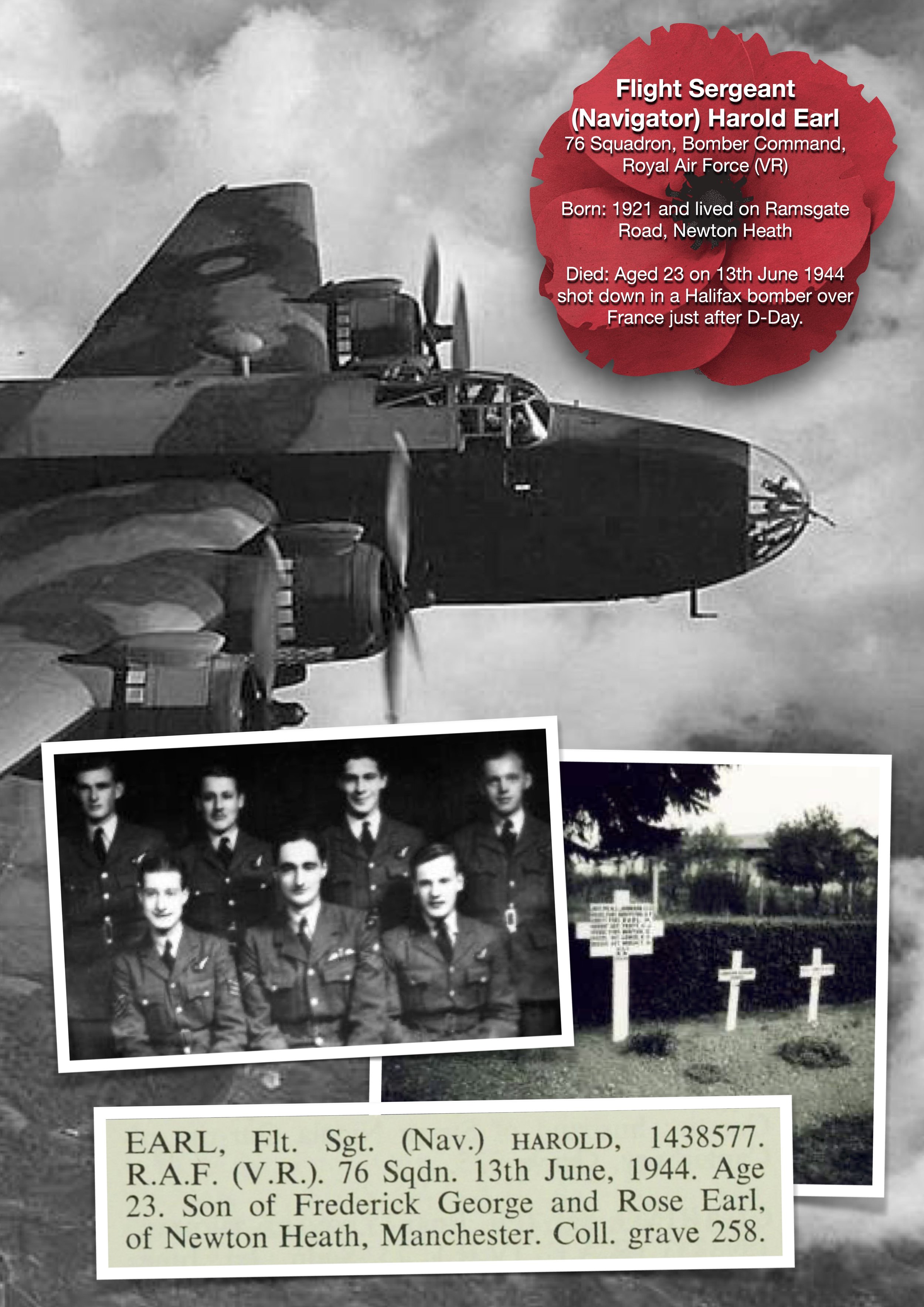

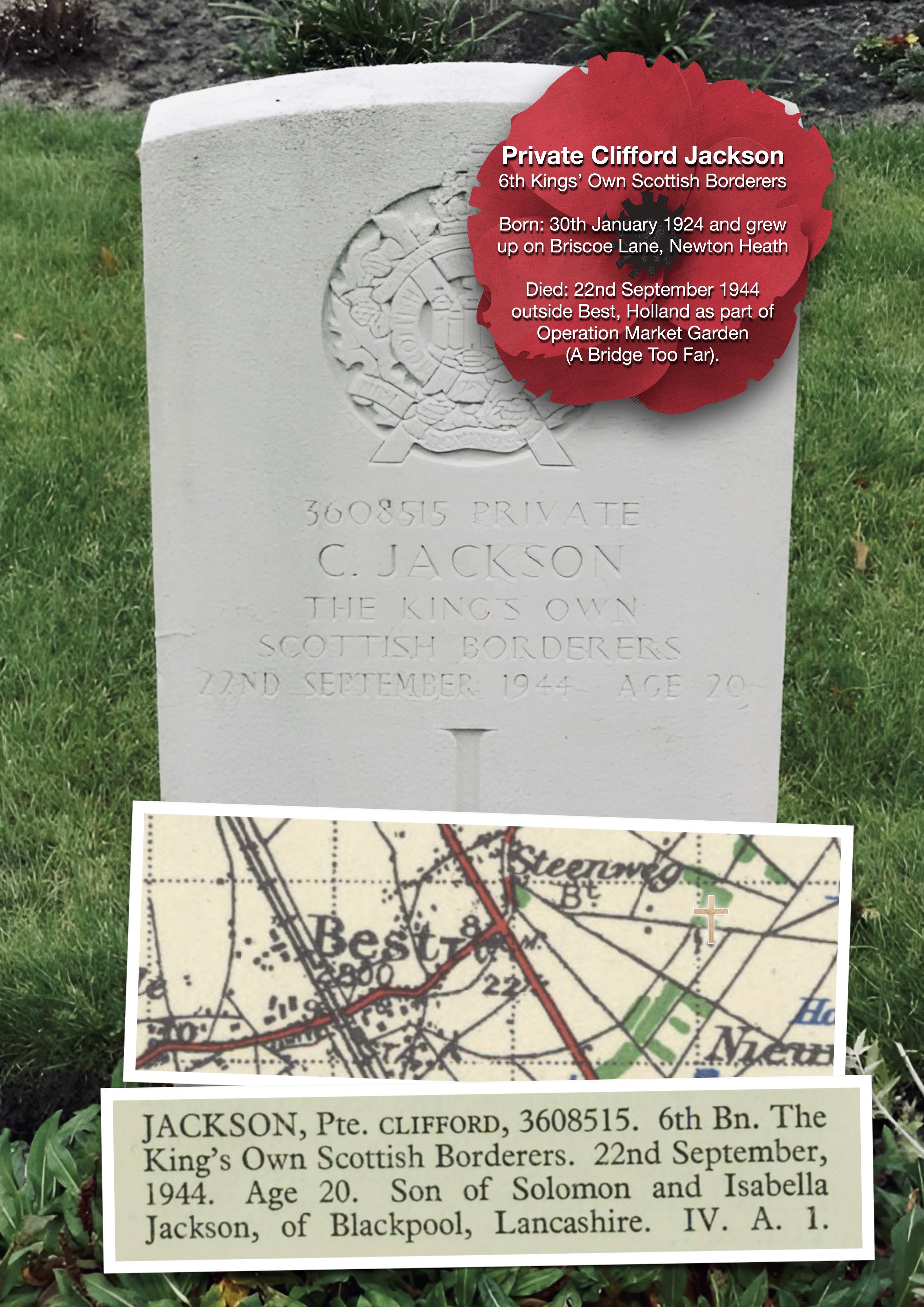

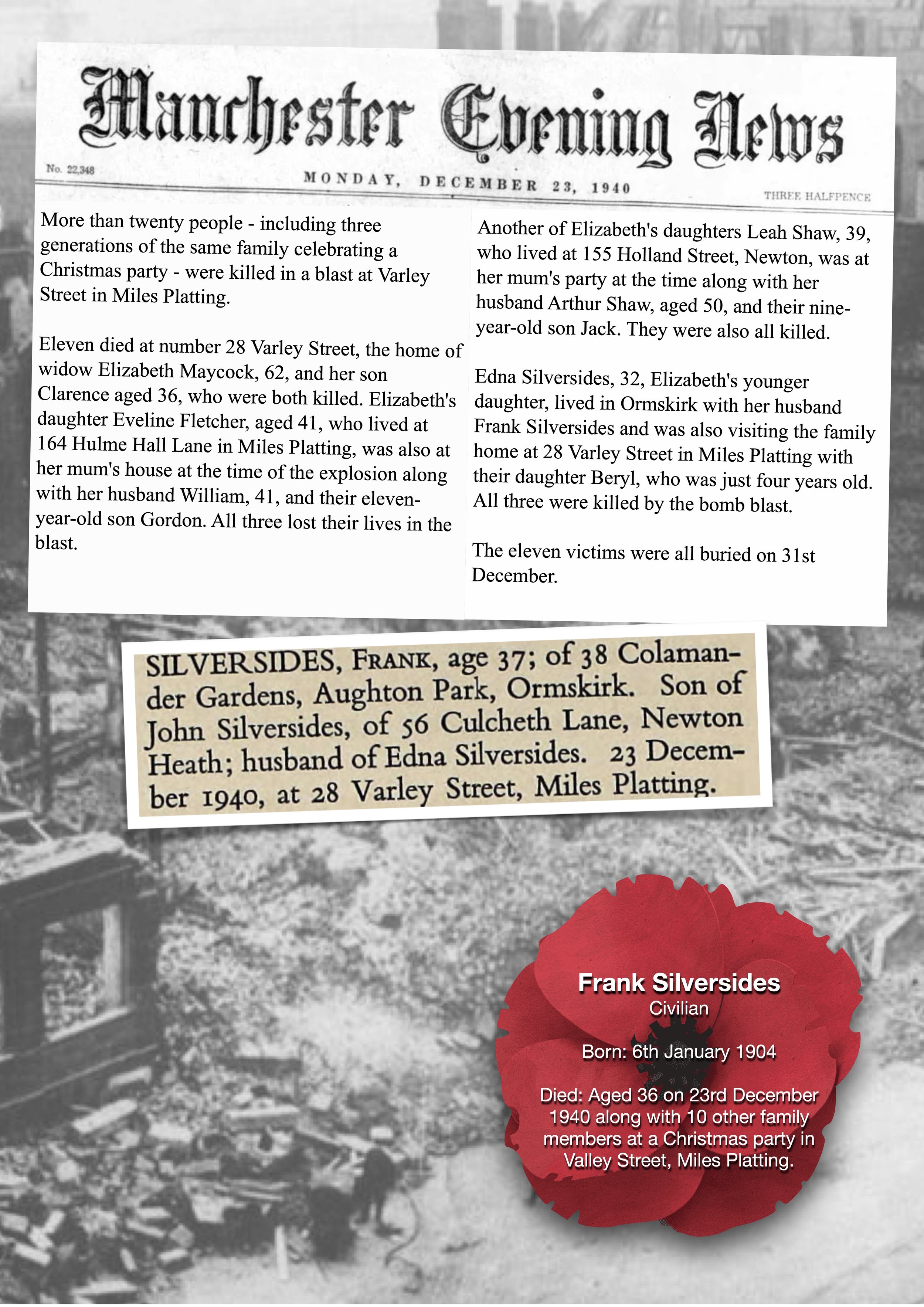

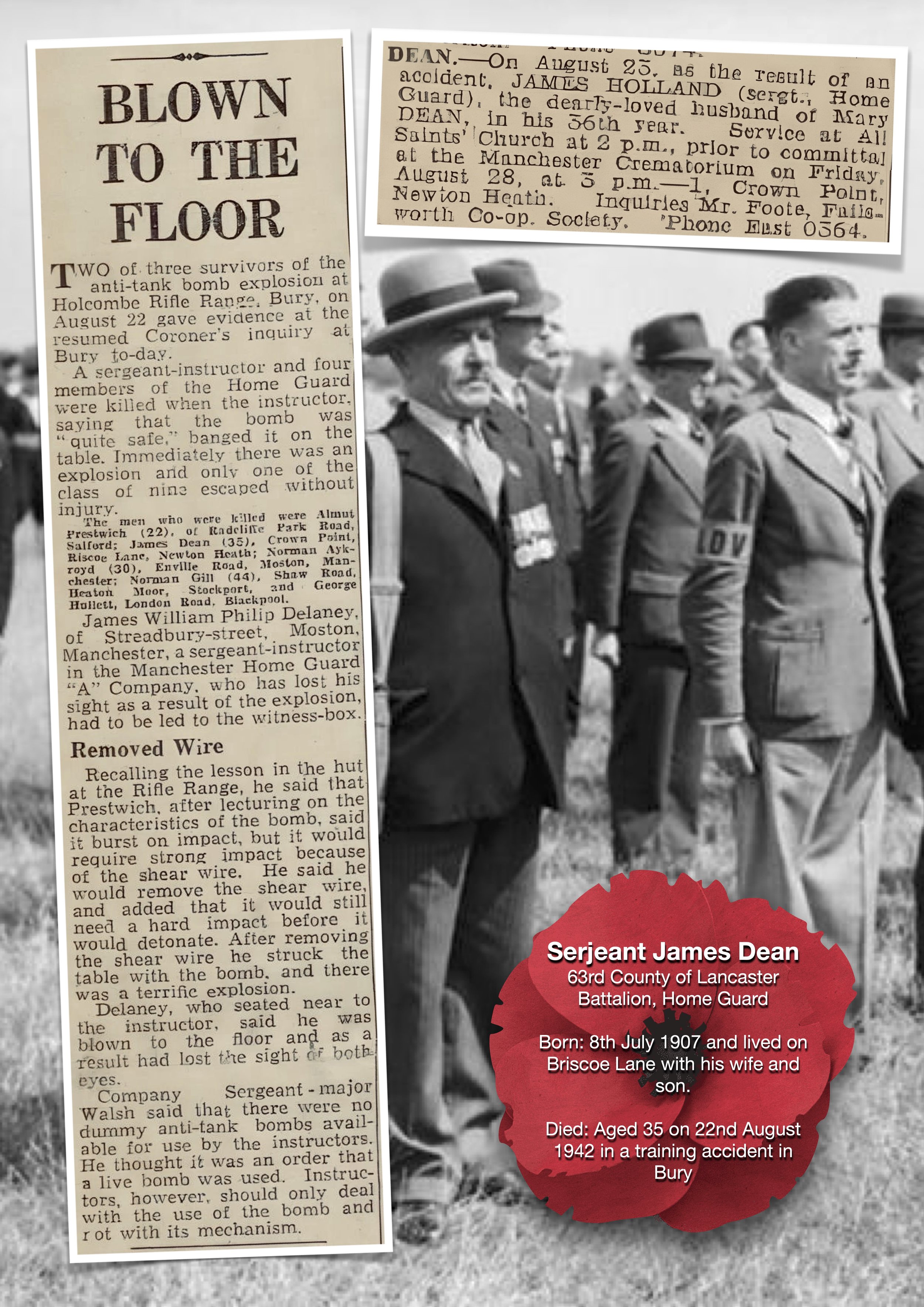

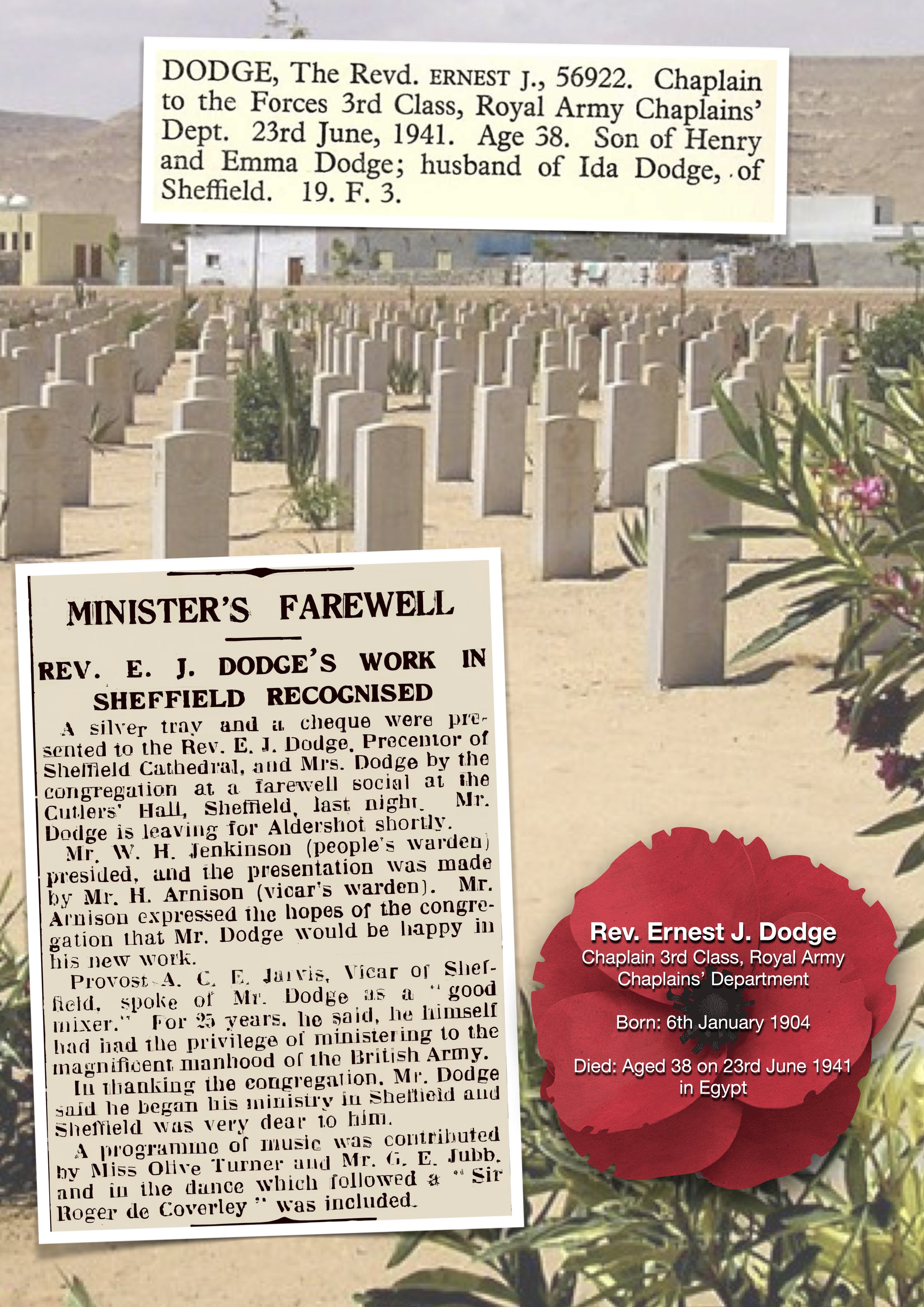

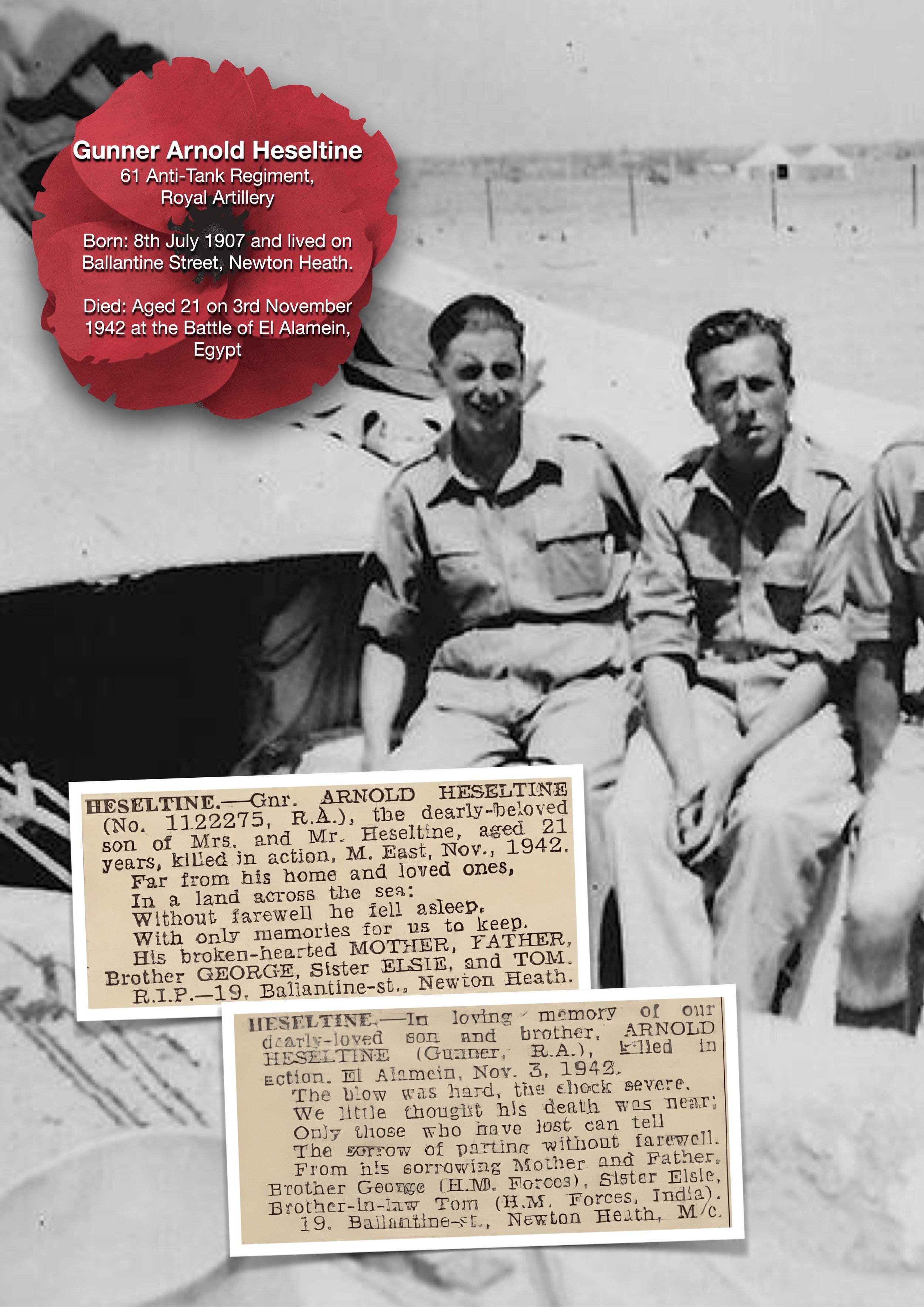

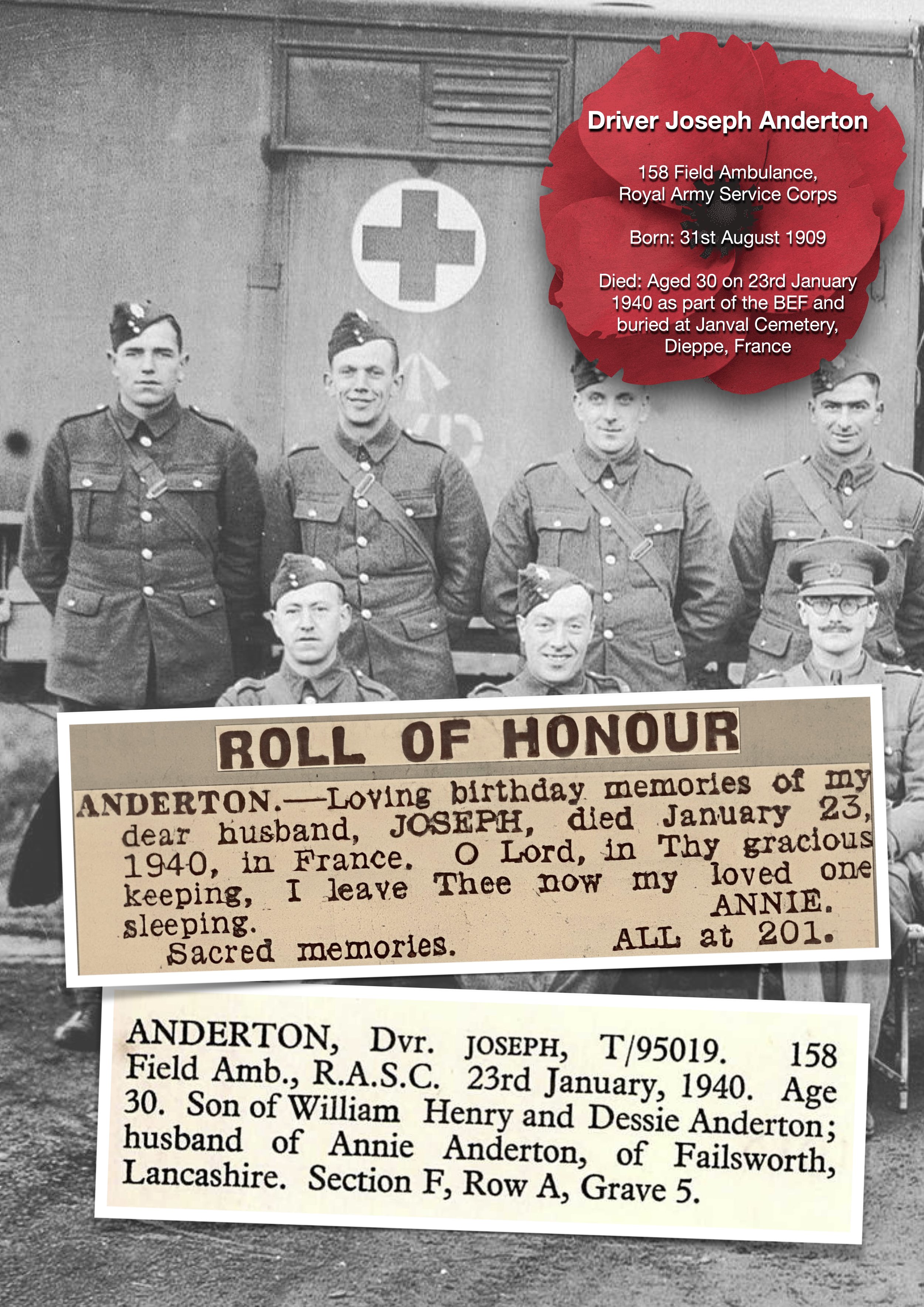

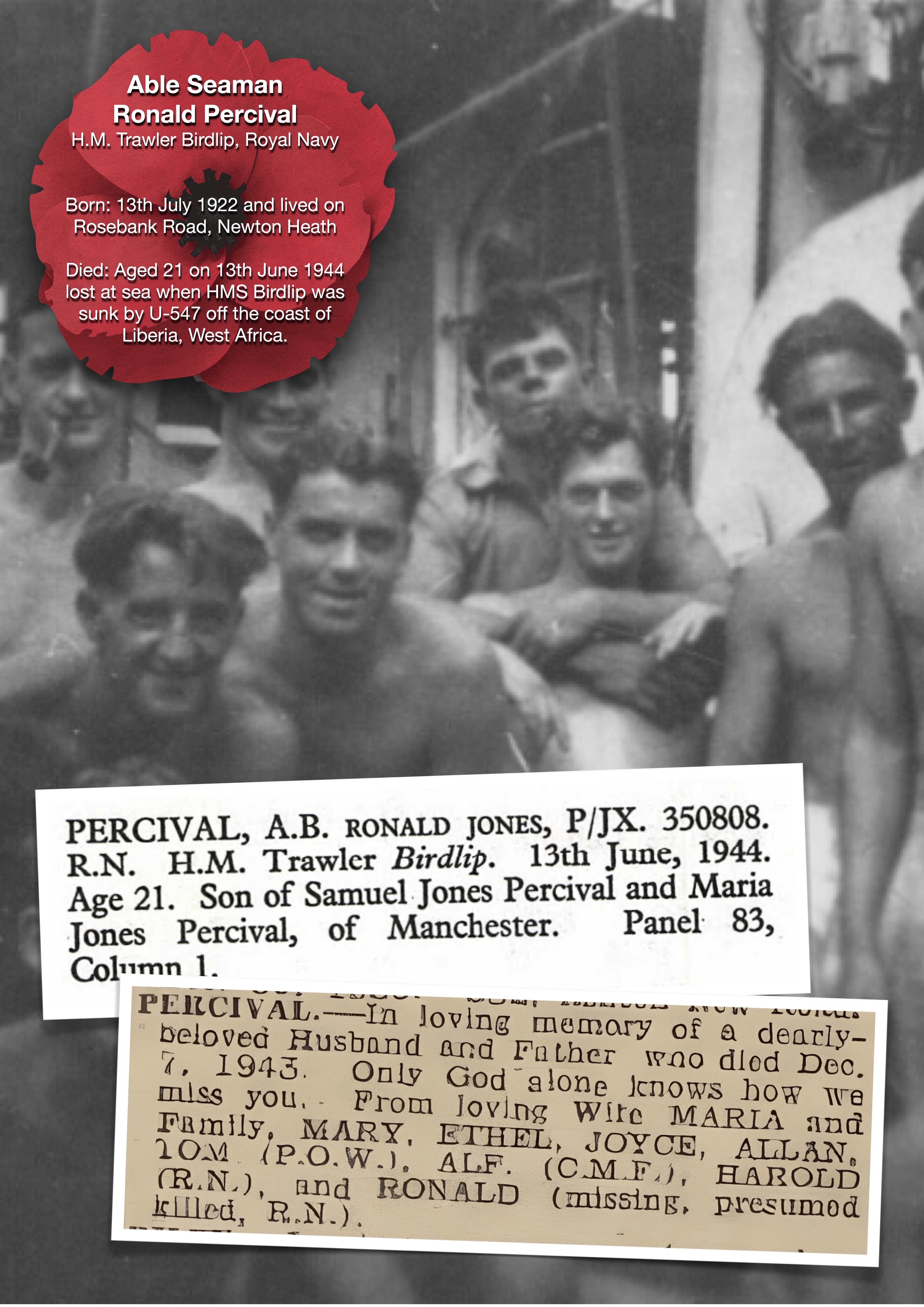

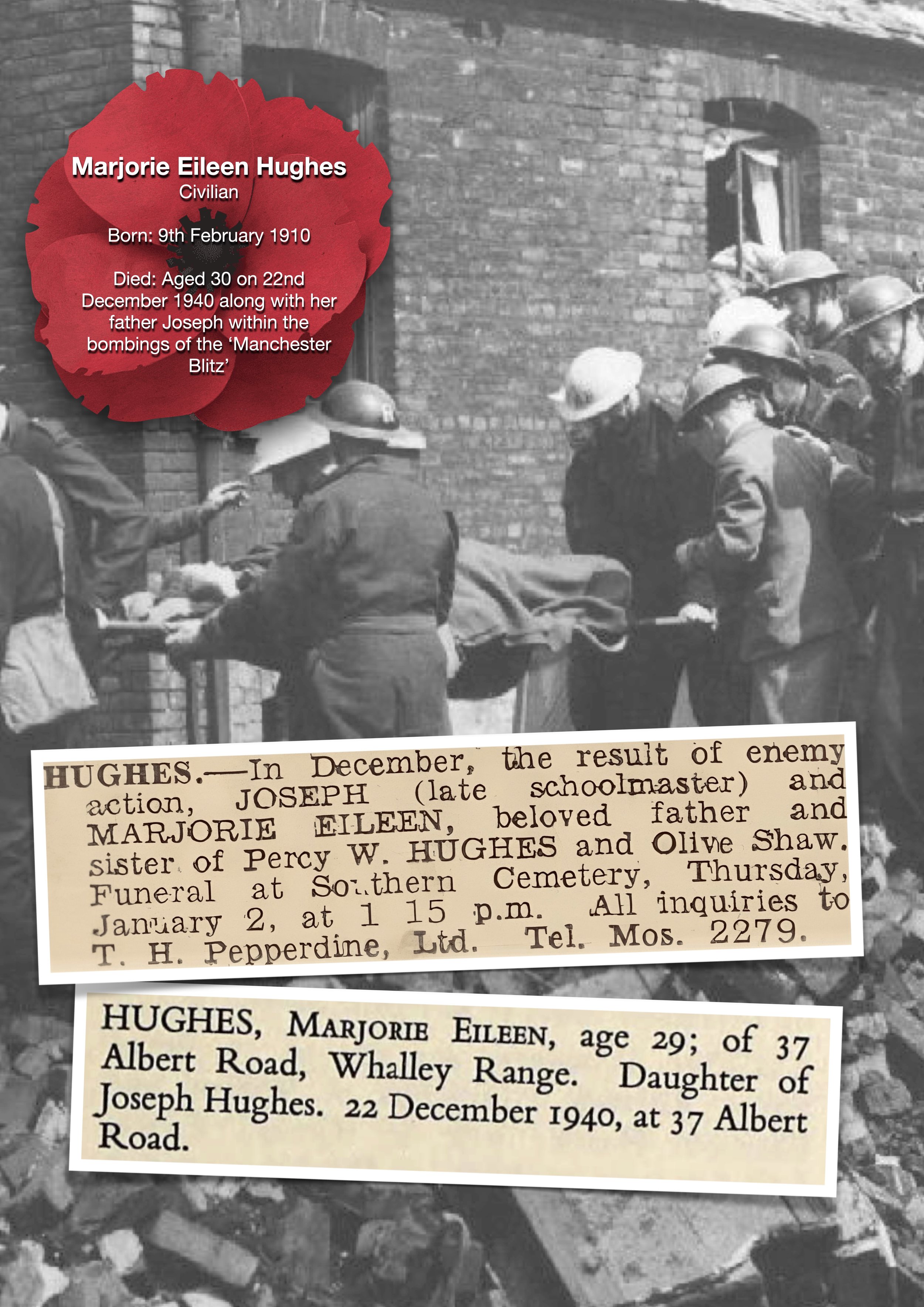

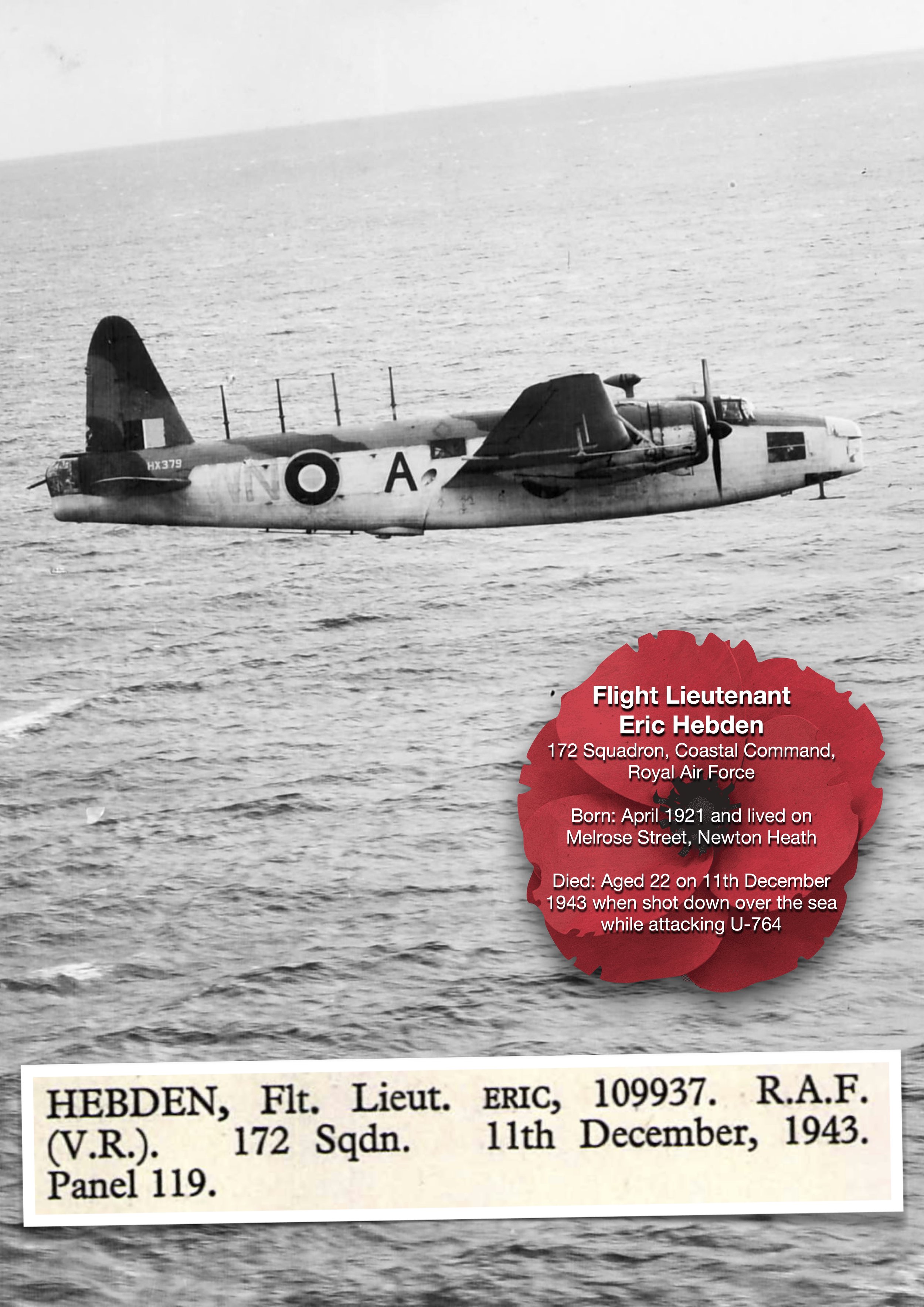

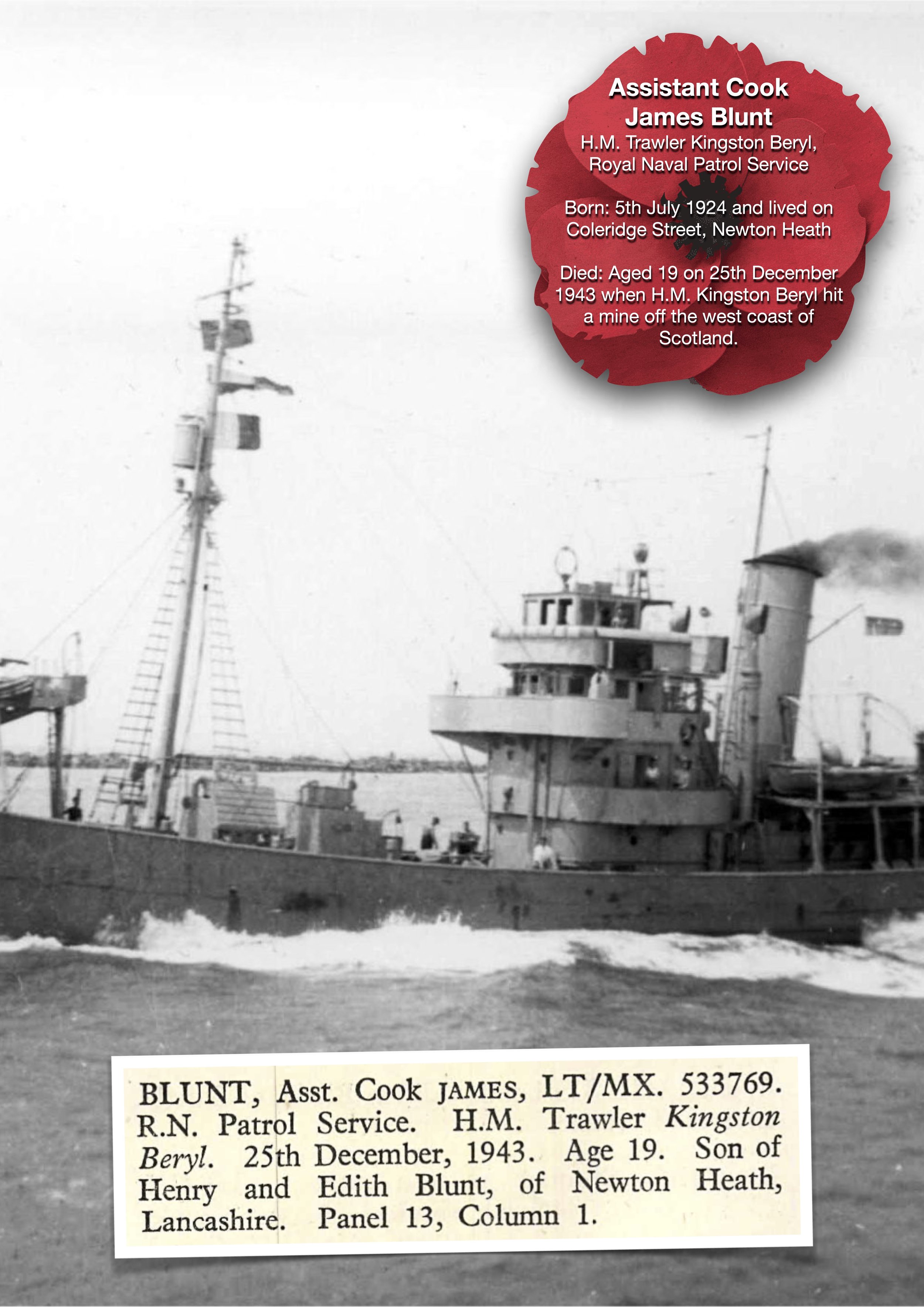

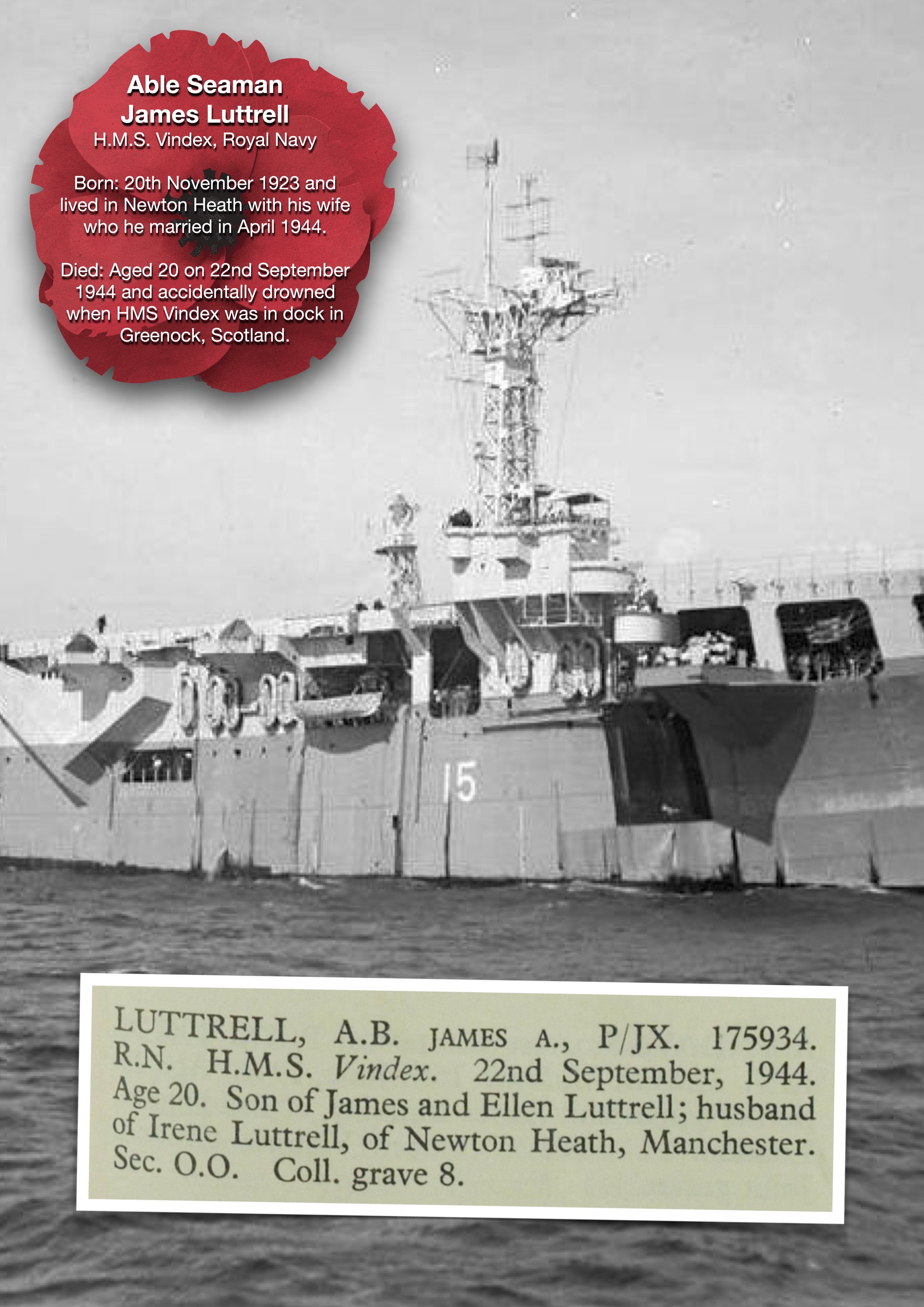

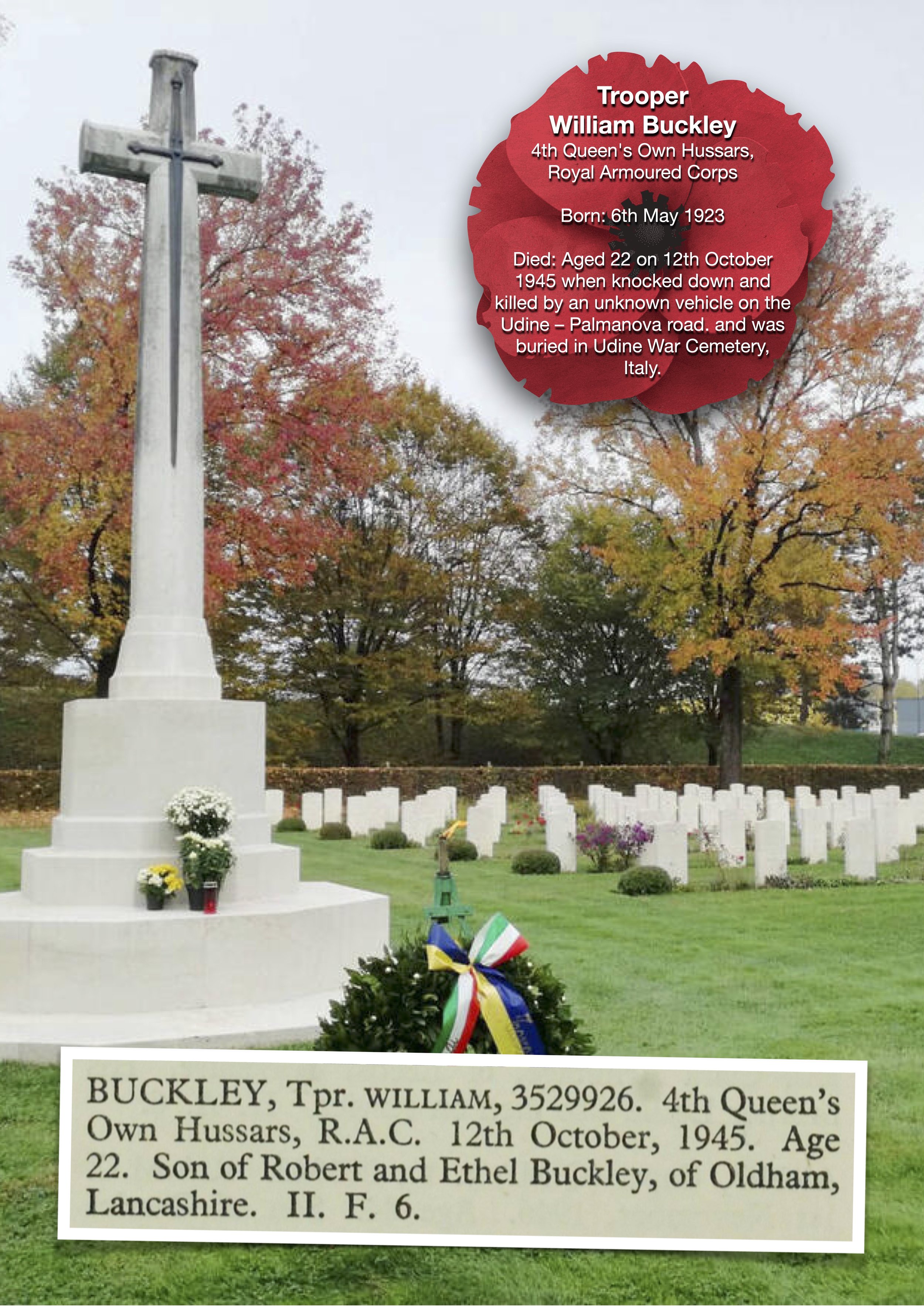

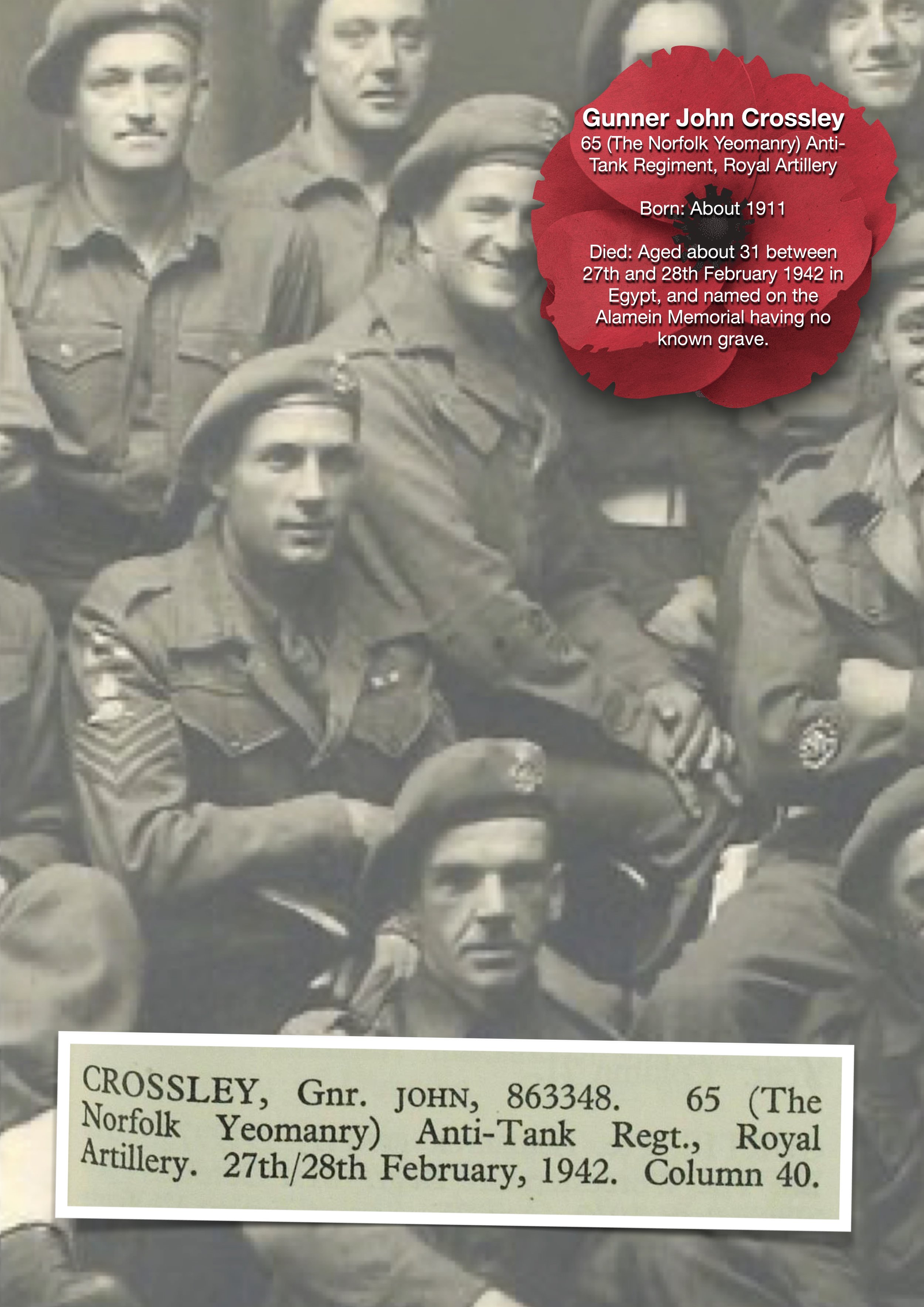

World War 2

The school archives show that the children of the school were evacuated on 1st September 1939 to Fulwood outside of Preston.

This first account is by Frank White who was a 12-year old chorister at All Saints Church in 1939, and is a very powerful account of the fateful day when our children were evacuated out of the city.

On September 3rd, two Sundays later, at noon, on leaving All Saints church, Newton Heath, Manchester, where I was a chorister, I walked to the place where my father had an allotment. On my way the information reached me that, during Matins, while we in the choir had been singing Psalm 18 (‘The earth trembled and quaked : the very foundations of the hills shook…’) war had been declared.

My father was in his greenhouse, side-shooting tomato plants, and I gave him the news. He’d been one of that first 80,000 professional soldiers who’d gone to France with the British Expeditionary Force at the beginning of the First World War and he’d fought on through Mons, Marne, Aisne, First Ypres, Festubert, Loos and the Somme, until wounds ended his war. He knew better than most what the news meant. He sank on to the wall of the greenhouse trough and tears welled up in his eyes.

The evacuation of the schools had taken place over the previous three days. Like the irresistible siren strains of the Pied Piper, it had emptied the streets of children. I was one of the very few who stayed behind. On a bright, cloudless morning, I went to the local primary school to see the evacuees off on their way.

Three red, Manchester Corporation Transport Department double decker buses waited at the kerb while their drivers stood together some distance off, smoking in silence.

On the pavement, huddled together, jostled the evacuees, over a hundred of them, all aged eleven or under, with their cardboard gas mask boxes slung by string over their shoulders, their name tags pinned to their chests, and, here and there, paper carrier bangs dangling from their hands, containing, no doubt, emergency provisions for the journey.

Among them, fussing, straightening children’s caps, fastening buttons, staring into children’s faces, milled their parents, some fathers, many mothers. At the periphery, and sometimes elbowing their way into the crowd, half a dozen agitated teachers with lists in their hands and tense faces, called out names and tried to shepherd this group or that out of the crowd, but the noise was such that for a while no-one appeared to hear them. Onlookers, with arms folded, stood at their garden gates, and shopkeepers had come to their doors, to watch it all.

The din, the confusion, went on for a good ten minutes longer until, mysteriously, in little spasms, as if someone with a volume control was slowly turning down the knob, silence began to spread. Last minute doubts, uncertainty and reluctance, were fading and a sad sense of inevitability was setting in.

For a while no-one seemed to move. Then, galvanizing themselves again, the teachers, with outspread arms and loud shouts, began to gather their charges, parting them from the tearful hugs of their parents, lining them up in three shuffling columns, and feeding them at last on to the buses.

Many younger ones were crying. Others moved as if in a trance, baffled and uncomprehending. Others, older boys, unwilling to show emotion in the sight of their mates, grinned, rocked their shoulders, and refused to look back. Two sisters had been selected for different buses. They themselves didn’t seem to care, but their mother screamed and ran about hysterically until she saw them sitting side by side

A boy I knew, thin, long haired, Jim, a ragged lad whom I sometimes found trailing after me for no reason, saying nothing, had neither father or mother with him. But I had the distinct impression that he was enjoying this, looking forward, glad to be going. On the platform of the bus he turned to offer me a cheerful smile and a wide wave goodbye. From both decks of all three buses, the children gazed out. With drawn faces and fluttering hands, the parents gazed back, mouthing last messages. Others, whose children were on the other sides of the buses, crossed the road and waved from there. And at last the buses drew away.

“Tarra! Tarra! Tarra!’ called the parents, with crumpled faces and wet eyes. “Tarra, love, tarra, tarra tarra…!’

And the buses, like a squadron of battleships in line astern, sailed out of sight down Briscoe Lane.

For a while yet the parents lingered, sometimes conversing in quiet voices, sharing their misery, sometimes merely standing there unable to move away. But at last they all drifted off, leaving me sitting on the low wall under the privet hedge. Just as I got up the caretaker of the school came to close the gates. I watched him fix them firmly together with chain and padlock. Then I tramped away.

The next account is by James, who was a pupil at the school who evacuated to Fulwood. One can only imagine the trauma the parents and the children felt.

My memories start when I was ten years old and lived in Manchester. Two days before war broke out we were evacuated.

We moved from All Saints School to a school in Fulwood, Preston. Some of our teachers also went along with us. Three of my family were evacuated - myself, my younger brother and my elder sister. We arrived at the school in Fulwood, where we were divided among families. The three of us were kept together and went to a family with the name Nye.

We stayed with them for six months. After this we were split up. I went to a family who lived in a large farmhouse and had seven other evacuees. We all did our share of the chores and were very well looked after. I stayed with this family for three years although I did go home and visit my own parents about three times. Even after the war ended, I visited the family and stayed with them for a couple of days.

I went to school, mornings one week, afternoons another. A Methodist chapel was converted into school rooms for us. I remember the school produced a school magazine called 'The Evacuee'. We put our own words to popular songs and they were printed in the magazine. We also wrote articles in it telling of our own personal experiences. Also, while at the school in Preston, we were joined by evacuees from South London. We soon realised that we talked differently but got on very well together.

I remember in Preston there was a large aircraft factory and during the war it regularly got bombed and we'd been moved there for our own safety!!

The next account is from Fulwood Methodist Church, who did so much to look after the needs of the children whilst evacuated.

War was declared in 1939 and there were dark days ahead. Mothers and children were evacuated from London and Manchester and billeted in Fulwood homes. Our premises were used as a day school and the evacuees also attended Church and Sunday School.

Lancashire County Council established a Library in the room alongside the kitchen which still bears the title today. The room on the left of the entrance porch was “The Firewatching Room”. Six bunks were installed and there was a firewatching rota. Six young ladies from Fulwood kept watch every Friday night after the dustmen on Thursday night. The A.R.P. Wardens on duty would call in for supper at 10 o’clock.

The Government felt that something must be done to occupy the children and young people in Wartime. At Fulwood it was decided to start the uniformed organisations and Brownies, Cubs, Guides and Scouts met for the first time in 1942. The Rev. A.E. Foley vigorously encouraged these activities and brought the Youth Centre into being. Classes for Folk Dancing, Drama, Handicrafts, Badminton and Table Tennis were held each night of the week. The Sunday School which met on Sunday afternoon decided to start the “Order of the Morning Star” to encourage the children to attend Church on Sunday mornings. The Junior and Senior Guilds had ceased to meet in the mid 30’s and although there was an “Inters” Guild for a short time it was not until 1945 that the Wesley Guild was re-established.

After the first few months of the war, some children returned to All Saints but to a very different school. The lower floor, which usually housed the infant department, had bed been converted into an air raid shelter which was not removed until 1945. Some of the teachers were employed to teach the children, and some of them also went to Fulwood with the children for a period of time. What dedication!

At the end of the war, the school archives show that teachers returned from ‘active duty’, but to a different school to the one they left.

After the Education Act of 1944, the school would become All Saints Primary School, and replaced the infant and mixed schools, and Miss Taylor who had been the headmistress of the infant school, would become the first Head Teacher of the primary school and would be in post for over another 20 years.

Do you agree with capital punishment? It was abolished in England in 1969, but some people would like to bring it back. What do you think?

“... is said to be a deterrent. I cannot agree. There have been murders since the beginning of time, and we shall go on looking for deterrents until the end of time. If death were a deterrent, I might be expected to know. It is I who have faced them last, young lads and girls, working men, grandmothers. I have been amazed to see the courage with which they take that walk into the unknown. It did not deter them then, and it had not deterred them when they committed what they were convicted for. All the men and women whom I have faced at that final moment convince me that in what I have done I have not prevented a single murder.”

Harry Thorneycroft MP

Harry Thorneycroft MP

The Daily Dispatch, Thursday 8th March 1945

Harry Thorneycroft was born in Newton Heath in 1892 and attended our school around the turn of the 20th century while living in Ballantine Street.

He worked as a hairdresser from the age of 9 near the entrance to Brookdale Park on Droylsden Road. He later became President of the National Federation of Hairdressers.

During the First World War, he served overseas with the Royal Field Artillery, and while living in King Street, Newton Heath (near where Lastingham Street is now) he was elected as a councillor to Manchester City Council in 1923, and became an alderman in 1939.

Daily Herald, Friday 16 October 1942

After trying to become an MP in Blackpool in 1935, Harry was elected to Parliament seven years later as a Labour Party MP at a Manchester Clayton by-election in October 1942, after the death of the Labour MP John Jagger.

During the Second World War, the parties in the coalition government did not contest by-elections when vacancies occurred in seats held by their coalition partners, but in the Clayton by-election Thorneycroft was opposed by an independent candidate, Major Hammond Foot.

Thorneycroft received a letter of support signed by the Prime Minister, Winston Churchill, and the leaders of the other coalition parties. He was the first Labour candidate to receive such a letter, and won the seat with 93.3% of the votes. He held the seat until the constituency was abolished for the 1955 general election, when he retired from Parliament.

Relaxing on the Terrace at the House of Commons

From 1945 to 1947, he was Parliamentary Private Secretary (PPS) to Lord Pethick-Lawrence, the Secretary of State for India and Burma. He was then PPS to Arthur Henderson, the Secretary of State for Air, from 1947 until the Labour Government left office in 1951.

He died in hospital in London on 7 March 1956, aged 64.

Education Expands Again

In 1947, under the Education (Butler) Act of 1944, All Saints became a Voluntary Aided Maintained Primary School associated with Manchester City Council Local Education Authority. This brought voluntary schools further under the control of government, but allowed them to keep certain ‘freedoms’ such as their religious character, admissions criteria etc. It also left them responsible for the cost of maintaining the buildings and grounds (although grants would be provided).

It also marked the end of the school having two Head Masters/Mistresses, one for the infants and one for the mixed school. The leaving age was brought down to 11 and the school became one primary school. Miss D. Taylor, who had been the Head Mistress of the infant school since 1934, was appointed the first Head Teacher of the primary school and would continue in this role until 1965.

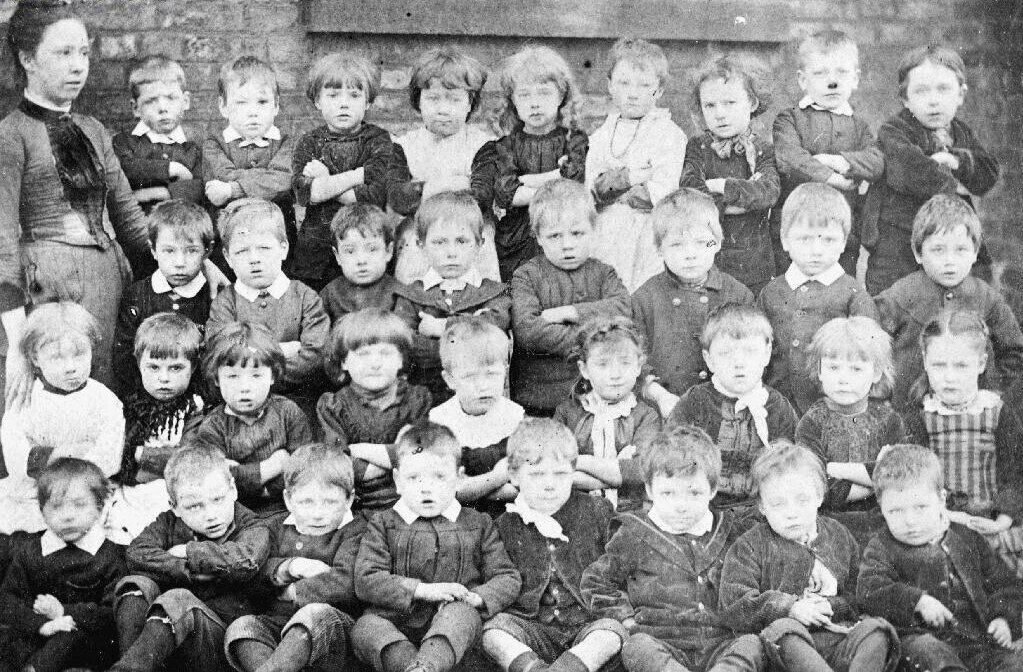

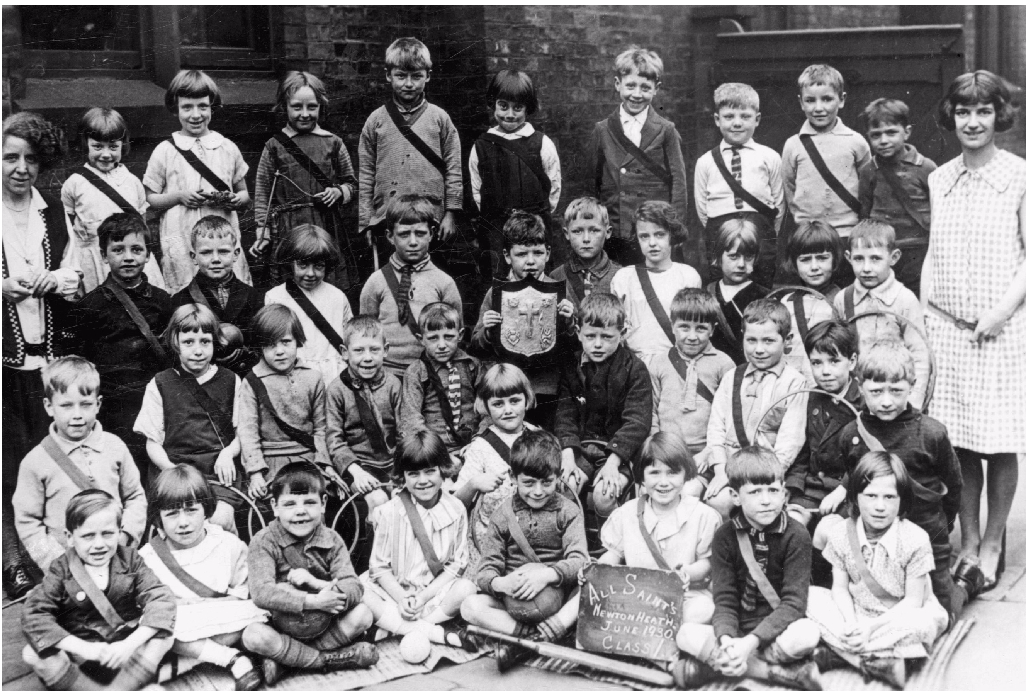

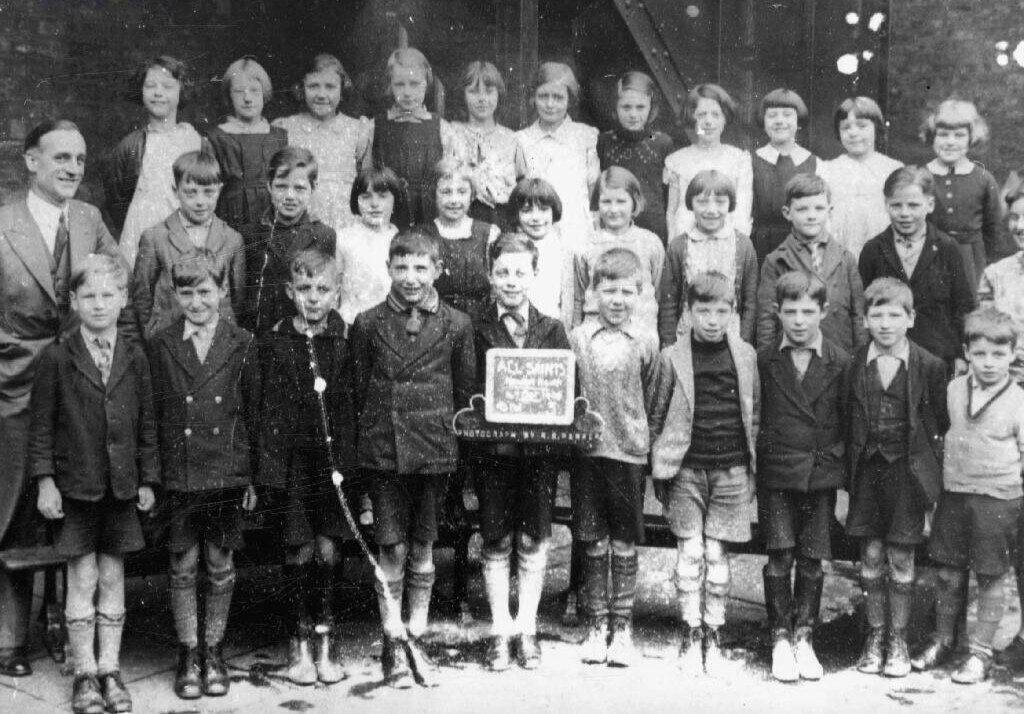

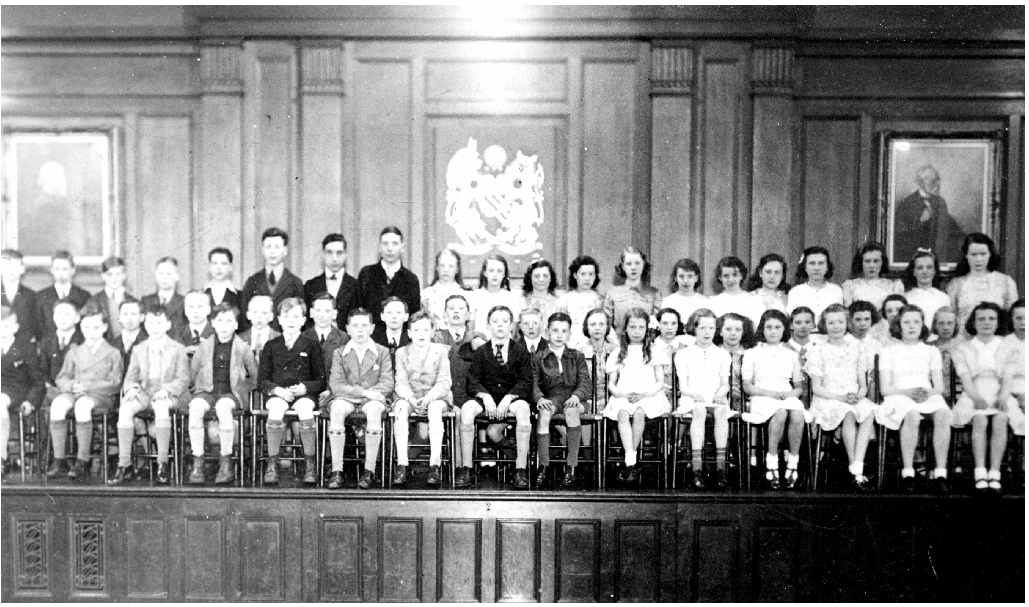

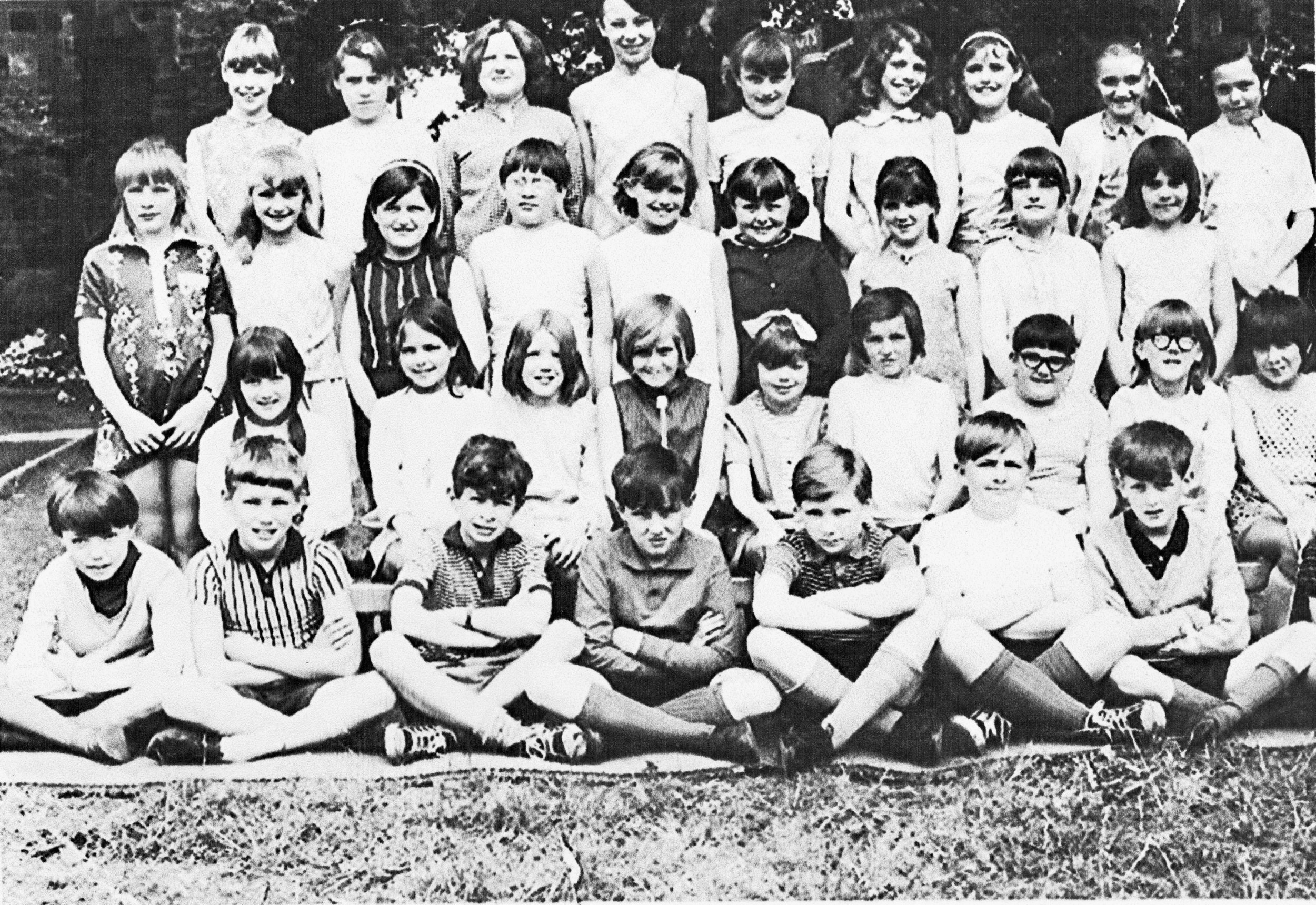

School photos through the years

400 Years of All Saints Church

A New School

In the late 1940s and early 1950s, the governors of the school had reluctantly accepted the plans set out by the Local Authority, to close All Saints School. The building was around 100 years old and not fit for purpose anymore. The governors could not afford to make the changes necessary, and that they thought was that. However, thankfully the school was saved under new plans in which the old school site would be developed along Church Street. There were various plans made, but none were satisfactory.

A new modern school was needed and to make way for the new building, the old rectory (now the Nursery area) was demolished and a new one built at the top of Briscoe Lane. Along with this, the old graveyard area was used to provide a playground (currently the KS2 playground) and is still owned by the church today. The bodies within the graveyard were exhumed and reburied in Philips Park Cemetery. This is also the case for thousands of bodies buried in the extension cemetery, which is now the Orford Road Community Park.

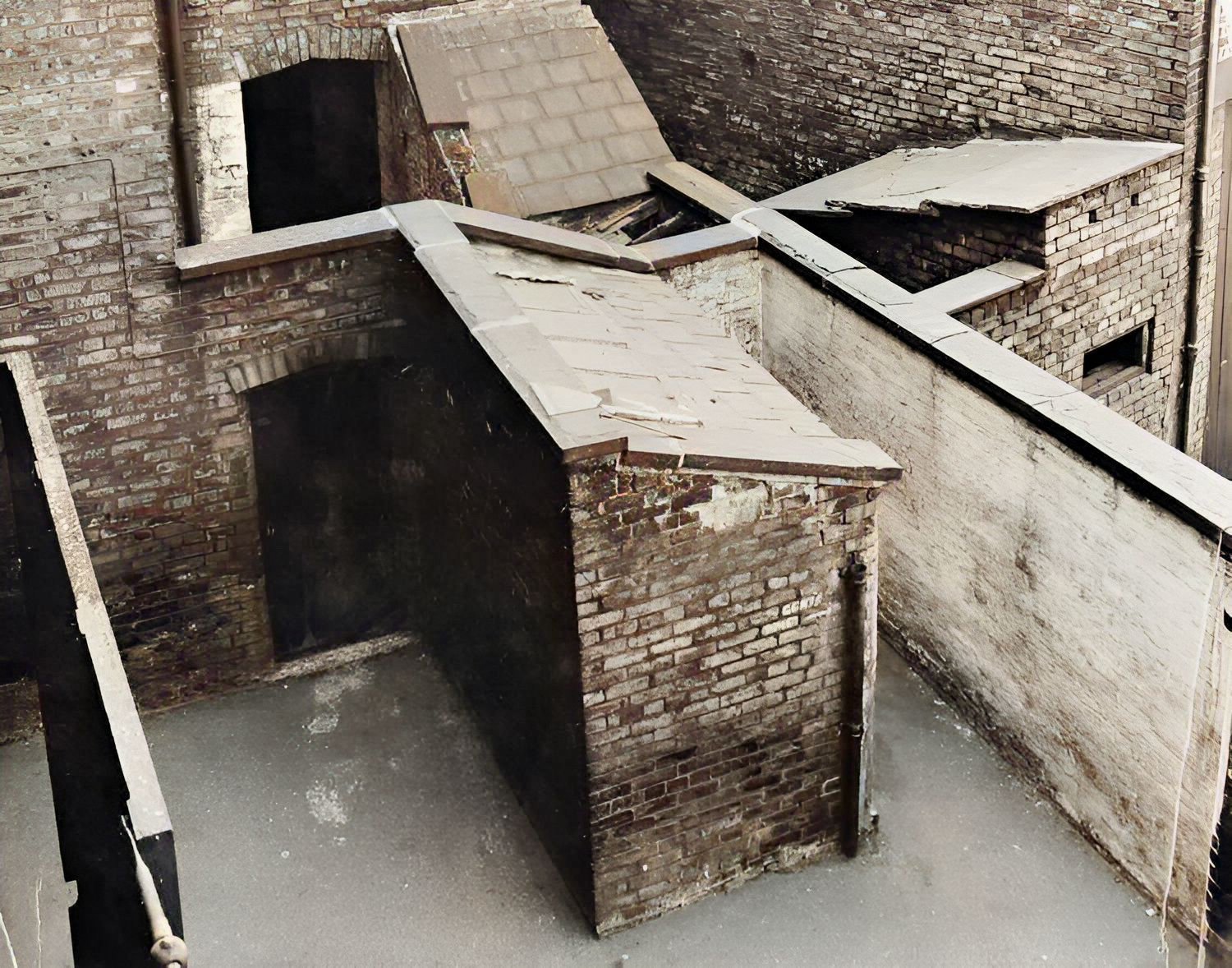

The 1854 school was demolished a few laters later and is now the site of the Peace Garden and Remembrance Memorial.

The images above show the changes between 1958 and today. The land owned by the church, which used to be the graveyard and the rectory and garden, was used for the school building and KS2 playgrounds (leased to Manchester City Council). After the building was opened, Manchester City Council bought one half of Church Avenue and demolished the houses to make way for what is now the KS1 playground.

Councillor Kathleen Ollerenshaw laid the Foundation Stone on 25th July 1963. This can be seen today opposite our office in the main entrance.

Goodbye to the 1854 School

The new school opened to the children in 1964, and at a later date, houses in church terrace were demolished to make way for what is now the KS1 playground.

Photographs from the 1960s and 1970s after the current school building opened.

Find out more about COVID-19.

Redevelopment

The Etihad Stadium, home to Manchester City, was originally the main stadium for the 2002 Commonwealth Games and is the centre of Sportcity. It was then repurposed for Manchester City, and has been expanded since. There is also a smaller stadium and large training complex which forms part of the Etihad Campus. A new indoor arena is also being constructed closer to the end of Briscoe Lane. Click the image to find out more.

Reflection

“The general characteristic of the natives of the Newton Chapelry District is a slowness of speech, which is most marked in those of Failsworth. They speak with drawling intervals, reflecting the impression on the minds of generation after generation of hand-loom weavers of the rhythmic throw of the shuttle and movement of their treddles, with the perpetual sound of

Nicketty-Nacketty-

Monda’ com’-Saturda’.

In appearance they have a remarkable resemblance to one another, due to centuries of interbreeding. They be said to be as like one another as hounds in a pack. The features are rugged, and the expression is solemn, but with keenly observant eyes, due to constant alertness to defect flaws in the “cuts”.

Their stolidity is, however, only surface deep. It would take a smart Yankee to get the better of one at a bargain; and the nature of their employment, though in a way monotonous, has required the exercise of all their senses, and has led to a great power of concentration and thirst for knowledge.”

This evaluation from 1904 gives a very good example of the divide at the time between the well-educated and privileged wealthy, compared with the limited education and opportunities for the poor.

It still has some relevance today with the disconnect between people brought up in totally different circumstances, not even aware of those of others, never mind understanding them.

The rather patronising tone of this piece from over 100 years ago, does give some clues to the problem within its descriptions. It actually describes hard-working, resilient, smart and inquisitive people, whose work contributed to Manchester being a world city. What it doesn’t describe are the reasons for poverty and the control held by the wealthy. When you rent a house from the people who also employ you, and who also fund and influence the limited services in the area, opportunities are extremely limited.

Newton Heath has changed beyond recognition on a number of occasions, and certainly since 1904. The old industries have pretty much gone, housing has changed a number of times, families have left the area and new ones have made it their home.

How lucky the children are today that education, health, medicines, housing control, sewers, social security etc are provided and that the limits to their success are their own ambition and hard work.

There are still challenges to overcome, and the next generations can definitely overcome them and shape a new identity for Newton Heath.

To the future…